In Art, Be Pagan

Alice Gribbin has called for a remystification of art. Here's how to remystify.

Two decades ago, Robert Kaplan published Warrior Politics: Why Leadership Demands a Pagan Ethos. John J. Reilly reviewed it for First Things in 2002 and summed up the argument:

Kaplan is at pains to emphasize that he is not endorsing amorality, but rather a morality that is not Judeo-Christian. He calls this ethos “pagan,” though he asserts it formed the core of Winston Churchill’s ethics, not to mention the views of such nominally Christian political theorists as Machiavelli and Hobbes. The actual pagans he discusses at length are Sun Tzu, author of the fourth century b.c. Chinese classic The Art of War, and Thucydides. Warrior Politics is really a meditation on the ideas of these five men, plus those of Malthus, with reference to the needs of the twenty-first century.

The “warrior ethos” that Kaplan endorses takes something from each of them: Churchill’s animal spirits, Thucydides’ caution against arrogance, Machiavelli’s injunction to “anxious foresight,” Hobbes’ assessment of man as a dangerous predator, and the willingness of Malthus to consider that history need not tend toward the increase of human happiness.

Two decades later, the brilliant

published an essay that could have been titled “Warrior Muse: Why Art Demands a Pagan Ethos.”This is worth your attention in its entirety, but regard this glorious passage:

The future for art, if works of genius are to be realized, depends on art being remystified, both in the public psyche and in the minds of artists. Despite our longstanding misapprehension of art’s nature, the gods, as Ezra Pound knew, have never left us.

While this is worth exploring in itself, we who go back a ways recall a similar exhortation to re-enchantment that issued from Suzi Gablik in 1991. I read it not long after it came out, and the Kirkus review comports pretty well with what I thought of it at the time:

[Gablik] tries to trace the roots of the present crisis in aesthetics and to map out some ways of escape. Gablik's thesis is not original. “Since the Enlightenment,” she maintains, “our view of what is real has been organized around the hegemony of a technological and materialist world view...we no longer have any sense of having a soul.” Spirituality and ritual have been the first casualties of this attitude, but the most profound reordering, Gablik says, has occurred in the area of social relations, as the spread of individualistic philosophies has weakened or destroyed the cohesion of traditional communal structures—leading to the modern artist understanding his or her vocation in terms of the objects created rather than the audience addressed…. What is needed, we are told, is an aesthetics of “interaction and connection,” in which the artist works to restore the lost harmony between humanity and earth, and to override the alienation of race, sex, and class. At this point Gablik's argument falls into New Age obscurantism and is weakened further in that most of the exemplars of her approach (sculptors who design carts for the homeless, photographers who document toxic-waste dumping, etc.) sound more like social workers or advocacy lawyers than artists. A valuable analysis that brings forth incredible conclusions.

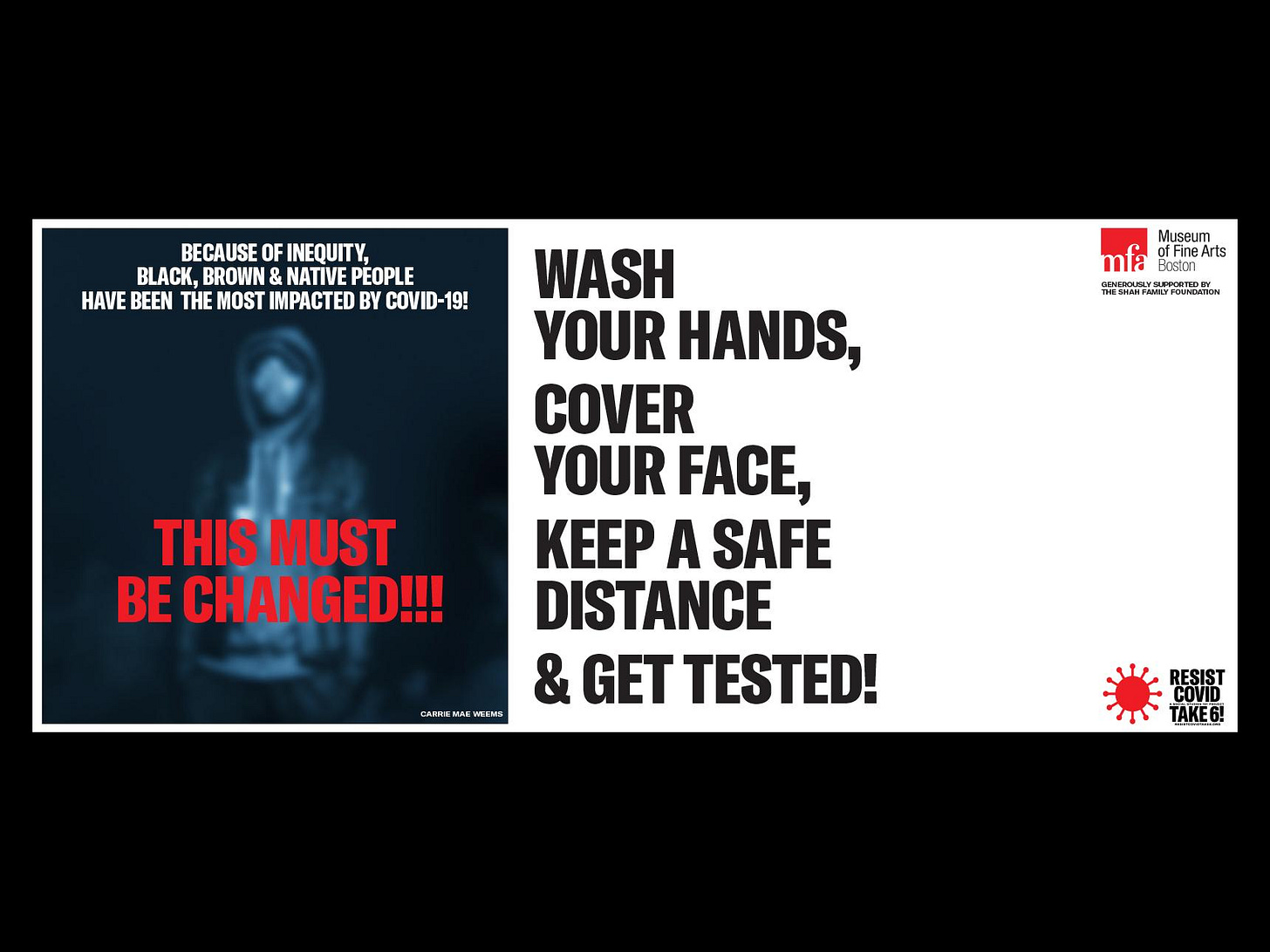

Without any sense of the divine, Gablik’s vision of aesthetic activism devolved into do-gooderism like 2021’s “RESIST COVID/TAKE 6!”, in which the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston defaced its own exterior with hectoring posters by Carrie Mae Weems that coupled woke racism with Faucian Lysenkoism.

Excepting the timeless advice to practice hand hygiene, every item on this poster including the title turned out to be wrong in some way, triple exclamation points notwithstanding.1 Germane to our topic, it is such an abject aesthetic failure that it even embarrasses the less-than-honorable history of visual propaganda.

This is to add to Gribbin’s irrefutable point here…

The gods are not slandered; they are utterly forgotten. To wave a hand and attribute this fact to secularism’s ascent over the past two centuries is inadmissible. Advanced over decades and from various directions, campaigns to demystify art—to make art legible, unmysterious, or more accessible—have obscured its nature, perversely. Those most involved in arts and culture have led the campaigns.

…that the campaigns have been led specifically by aspirants to Gablik’s re-enchantment. Accessibility was (and is) thought to re-form the communal structures that situate the artist in the wider social world, and through it, the natural world. Instead it reduces artists to bureaucrats, Kirkus’s ersatz “social workers or advocacy lawyers.” Artists cheat themselves and their audiences of the transcendent. In fact the transcendent is hardly suffered to exist, linked as it is to genius, which was associated for a long time in the West with tutelary deities. Gribbin, citing Linda Nochlin and others, alludes to the enormous efforts by art worlders to puncture the vaunted myth of genius.

I’m fond of a quote by Ludwig von Mises:

The champions of socialism call themselves progressives, but they recommend a system which is characterized by rigid observance of routine and by a resistance to every kind of improvement. They call themselves liberals, but they are intent upon abolishing liberty. They call themselves democrats, but they yearn for dictatorship. They call themselves revolutionaries, but they want to make the government omnipotent. They promise the blessings of the Garden of Eden, but they plan to transform the world into a gigantic post office. Every man but one a subordinate clerk in a bureau.

Add to this, they stood for re-enchantment but delivered art with all the soul of a filing cabinet. Mind you, the MFA characterized Weems as “one of the most important artists of our time.”

But if that’s the wrong way, what’s the right one? Gribbin is certainly hot on the trail of something important when, citing Hesiod, she encourages us to seek out the muses anew.

Here, near the beginning of this 2,700-year-old epic poem, we meet inspiration with all its meaning intact. The poet has been granted a new voice, verbally reanimated, by the Muses. Hesiod’s language is Ionic Greek. What has made its way to us is the Latin: in + spirare (from spiritus, “breath, or spirit”) becomes “into” + “(to) breathe.” The gods inspire the artist; they breathe into him their song.

But standing in the way of our connection to them is not just centuries of secularization, as Gribbin notes, but millennia of Christianity and Judaism, which she doesn’t. The longstanding iconoclasm of Judaism makes a Jewish basis for re-mystification hard to conceive.2 Christendom, particularly Catholicism, drew on Greece as a literary source, but the idea of worshiping her old gods with the fervor that one might devote to Jesus would have been regarded as intolerable.

Art of the Christian West was filled with pious mediocrities anyway, as was so brilliantly explored in Amadeus. Weems is one of the pious mediocrities of our new secular religion, in which covering your face is a mitzvah just as it is for a Jew to cover his head. Her image above implies that it serves the same purpose, which is understandable, once one realizes that the new religion has substituted equity for God. Masking confers as much protection from respiratory viruses as a kippah provides against sunburn, but there’s a faith to uphold. What, do you have something against black, brown, and native people?

To connect with the muses in a way that lets us feel their presence, we need a whole revision of attitude. We must accept a pagan catechism into our hearts which holds the following claims as truth.

1. Animism is real.

In animism, the natural world is seen as a complex web of interconnected beings, each possessing its own consciousness, agency, and spiritual essence. The associated spirits are believed to exist alongside and interact with human beings. Animistic beliefs hold that all entities, both visible and invisible, have their own unique spiritual force.

Shinto places great emphasis on the significance of nature and the divine power it embodies. According to the Kojiki, a Shinto text, the gods and goddesses are believed to reside in natural objects such as trees, rocks, and waterfalls. Artistic practice in Shinto is a means of connecting with divine forces and expressing gratitude for their beauty and power. “The gods created the arts to gladden the hearts of men,” says the Kojiki. The wabi-sabi aesthetic reflects the Shinto emphasis on the beauty of imperfection and transience, recognizing the inherent appeal of natural objects and natural processes.

I contend that you must feel this way about materials in order to make art out of them. When Darby Bannard wrote in the Aphorisms, “We have more in common with a rock than we think,” he was getting at something similar. Even if there’s not a distinct spirit in the rock, the process of creation that produced us also made the rock, and art on some level is a recapitulation of that process. It might as well have a spirit, since we do.

2. Inspiration is female.

By personifying the muses as women, ancient Greeks associated creativity, inspiration, and artistic expression with domains of femininity. When the muses dispense divine inspiration, they do so with a distinctly feminine spirit.

Accompanying that personification was an understanding that forcing women to do things against their will is a crime. As I wrote regarding Titian, one of lowest judgments issued upon the gods in the whole Metamorphosis regards Apollo’s pursuit of Daphne.

But though her father promised her desire,

her loveliness prevailed against their will;

for, Phoebus when he saw her waxed distraught,

and filled with wonder his sick fancy raised

delusive hopes, and his own oracles

deceived him.—As the stubble in the field

flares up, or as the stacked wheat is consumed

by flames, enkindled from a spark or torch

the chance pedestrian may neglect at dawn;

so was the bosom of the god consumed,

and so desire flamed in his stricken heart.

Far better is to win a woman’s consent through your valor, as Perseus did Andromeda’s.

I, Perseus, who destroyed the Gorgon, wreathed

with snake-hair, I, who dared on waving wings

to cleave ethereal air—were I to ask

the maid in marriage, I should be preferred

above all others as your son-in-law.

Not satisfied with deeds achieved, I strive

to add such merit as the Gods permit;

now, therefore, should my valor save her life,

be it conditioned that I win her love.”To this her parents gave a glad assent,

for who could hesitate? And they entreat,

and promise him the kingdom as a dower.

So it is with inspiration. Art may entail battle, but it is not itself a battle, but a seduction. Your art doesn’t necessarily become stronger by adding more square footage, more colors, or more exclamation points, but by satisfying a true purpose through courage and intelligence. At that point, inspiration may - may! - smile and offer herself to you.

If all this seems male-oriented and heteronormative, use your imagination in whatever manner works for you.

3. Intoxicants are holy, fun, and informative.

The consumption of soma, whatever it was, is a central aspect of certain rituals described in the Vedas. Followers of the Vedas believed that by consuming soma, imbibers could attain spiritual enlightenment, divine inspiration, and connection with the gods. They described its effects as uplifting and energizing, granting immortality and bestowing wisdom. Similarly, it is suspected that the Pythia was huffing some kind of geological source of ethylene at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi.

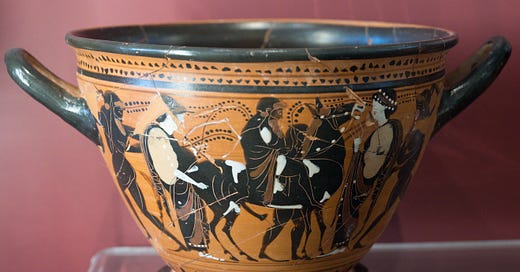

For that matter, Greeks were so impressed with the intellectually and spiritually liberating powers of wine that the word symposium originally meant “drinking party.” A whole Cult of Dionysus sprung up for which ecstatic dances, music, theater, and singing served as ritual.

Going even further, the Kojiki claims that “The gods of heaven and earth are all born of the divine essence of food and drink.” This amazing statement implies that the deliciousness of food and the intoxication of drink precede the gods themselves.

As something of a specialist regarding postwar American abstraction, I’ve read galling stories of alcohol abuse. Barbara Rose’s remembrance of Darby Bannard for Artforum includes this detail:

During the period that Larry Poons called the “vodka wars,” when Greenberg’s alcoholism increased while the insightfulness of his writing declined, Bannard wrote regularly for Art International, Artforum, and other art magazines, championing quality and the cause of high art in an atmosphere increasingly hostile to the idea, as if to make up for Greenberg’s absence in the critical dialogue.

I regard indulging in intoxicants to the point that they injure your talent, or injure the relationships that allow you to exercise your talent, as a sin. There is a middle way, and it’s not the Buddhist one of abstemiousness, but the deliberate production of insights, delight, and good cheer. One of my artist friends (that I know of) is a friend of Bill, and I respect his sobriety. He comes by insights, delight, and good cheer through other means.

Nevertheless it’s non-negotiable that an artist must open the channels to the irrational. Hopefully it doesn’t kill you. But as I have said, the price of art is high.

4. The gods are horny.

Zeus coupled with Hera, Metis, Maia, Semele, Europa, Leda (not to be confused with Leto, with whom he also coupled), Callisto, Ganymede, Io, Danae, Antiope, Thetis, Alcemene, and I can’t promise that’s the complete list. Shinto holds that the deities Izanagi and Izanami were instructed by still higher-ranking gods to procreate and populate the world. This act is described as the inception of Japan and the birth of numerous gods and goddesses. Supreme deity Olodumare created Oduduwa, the progenitor of the Yoruba people, with a mandate to form the Earth and humanity, which he accomplished through procreation with his wife Obutala. Hindus hold that union of Shiva and Parvati is fueling the entire cosmic engine.

Creation is sex-positive. Conduct yourself accordingly.

[Content at Dissident Muse Journal is free, but paid subscriptions keep it coming. Please consider one if you don’t have one already, and in any case thank you for your readership.]

“Take Six” in the title refers to the six feet of “social distancing.” The number was more or less pulled out of a hat, the ensuing silos only encouraged Covid to spread more aggressively through family units, and the social and economic isolation killed more people than the disease.

R.B. Kitaj comes close in his manifestos, but one may have to be Kitaj to put them to use.

It's not about being pagan but about being human and in touch with reality--and reality, the kind that has always been essentially the same and never changes, doesn't care whether you like it or not.

And yes, Franklin, your list of Zeus paramours is incomplete. You can add the nymph Aegina (to whom he presented as an eagle), for one, and I expect there are others.

Interesting exchange from a few years ago on Judaism, Christianity & myth

Michael Weingrad, 2010 >

https://jewishreviewofbooks.com/articles/290/why-there-is-no-jewish-narnia/

Follow-ups by Samuel Goldman & David P. Goldman [aka Spengler]

https://www.firstthings.com/blogs/firstthoughts/2010/03/christianity-and-myth-why-theres-no-jewish-narnia

https://www.firstthings.com/blogs/firstthoughts/2010/03/why-is-there-no-jewish-narnia