One of the opportunities afforded by the Manang Artist Residency was an opportunity to spend a day at Simrik Atelier, the Patan studio and school of the renowned Paubha master Lok Chitrakar. Chitra, चित्र, is “painting,” and kar, कार, is “maker.” Clan Chitrakar has been in the picture business in Nepal for centuries, though Master Lok is largely self-taught.

Paubha is a religious art from the Newar community of Nepal’s Kathmandu Valley. They are devotional paintings depicting Buddhist deities, mandalas, and religious narratives using mineral pigments on canvas. Artists follow strict iconographic rules regarding proportions, postures, and attributes of figures. Paubha works are patently illustrative, typically of Buddhist philosophical concepts. Tibetan thangka paintings are an analogous artistic development, though Paubha maintains a distinctive Newari style that you can recognize if you’re looking for it—the figures are softer and evince more Indian influence, the images occasionally reference Nepalese landscape or architecture, and sometimes a Hindu subject pops up. (Most of Nepal is Hindu, though it becomes more Buddhist as you travel uphill. I’m currently quite uphill, at 11,975 feet, and feeling pretty Buddhist.)

A one-day class on how to paint Paubha is about as hopeless a notion as a one-day class on how to paint a Dutch still life—students are known to spend a decade at Atelier Simrik—but it was enormously edifying and answered questions I’ve had about this kind of painting for years. Master Lok was kind and gracious, and I learned things that translate directly to my work in egg tempera.

To kick things off, we pounded a cinnabar rock into particles. Specifically, I pounded a cinnabar rock into particles. Here’s an eleven-second video of yours truly at work. After taking the rock down to pebbles and then dust, the dust goes into a stone mortar and is then pestled into a fine powder. That is then transferred to a ceramic mortar and pestled with water. Traditionally, one grinds the pigment with water for a week to achieve a proper dispersion. One is meant, in doing so, to grind down one’s ego to attain the proper state of mind for painting. I question whether that much grinding is necessary to achieve a good dispersion or sufficient to pulverize the ego, but that’s how they do it. After going through the steps of preparing cinnabar (they had some already made for us), we reduced some orpiment. I’ve never handled either in stone form or orpiment in any form. They’re beautiful at every stage. Paubha blues are indigo and lapis; dark red is cochineal, which has become all but unobtainable.

Pigment dispersions are finally mixed with glue made from the hide of a buffalo. It comes in chunks a centimeter thick and the area of a tortilla chip. Western rabbit skin glue is a similar material. Himalayan paint is described in the literature as bound with animal or vegetable glue; it turns out that the former is more typical. One can depend on the paintings being distempers, not gouaches. You can boil the hide glue, but it stinks up the studio (as one of Chitrakar’s students explained to me). Instead, they usually pour hot water over a piece or two of glue and stir it until it is dissolved. Dry colors re-wet with the introduction of liquid glue.

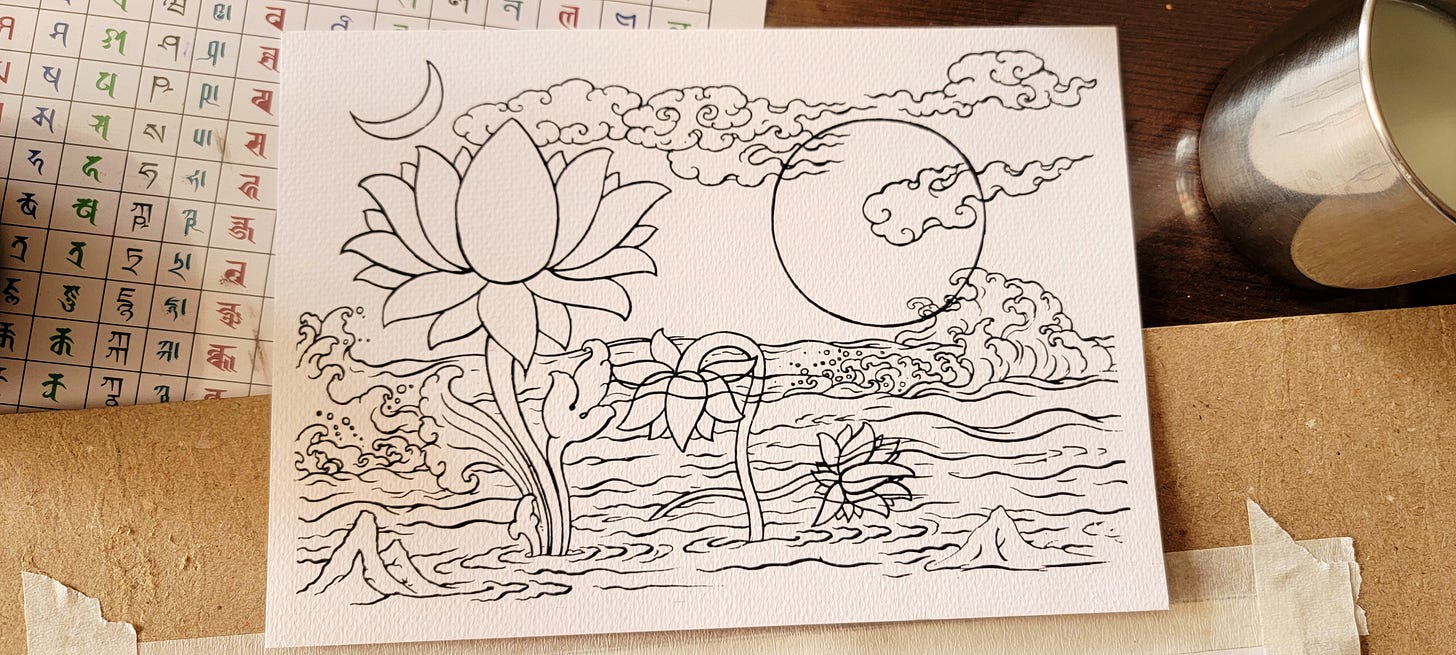

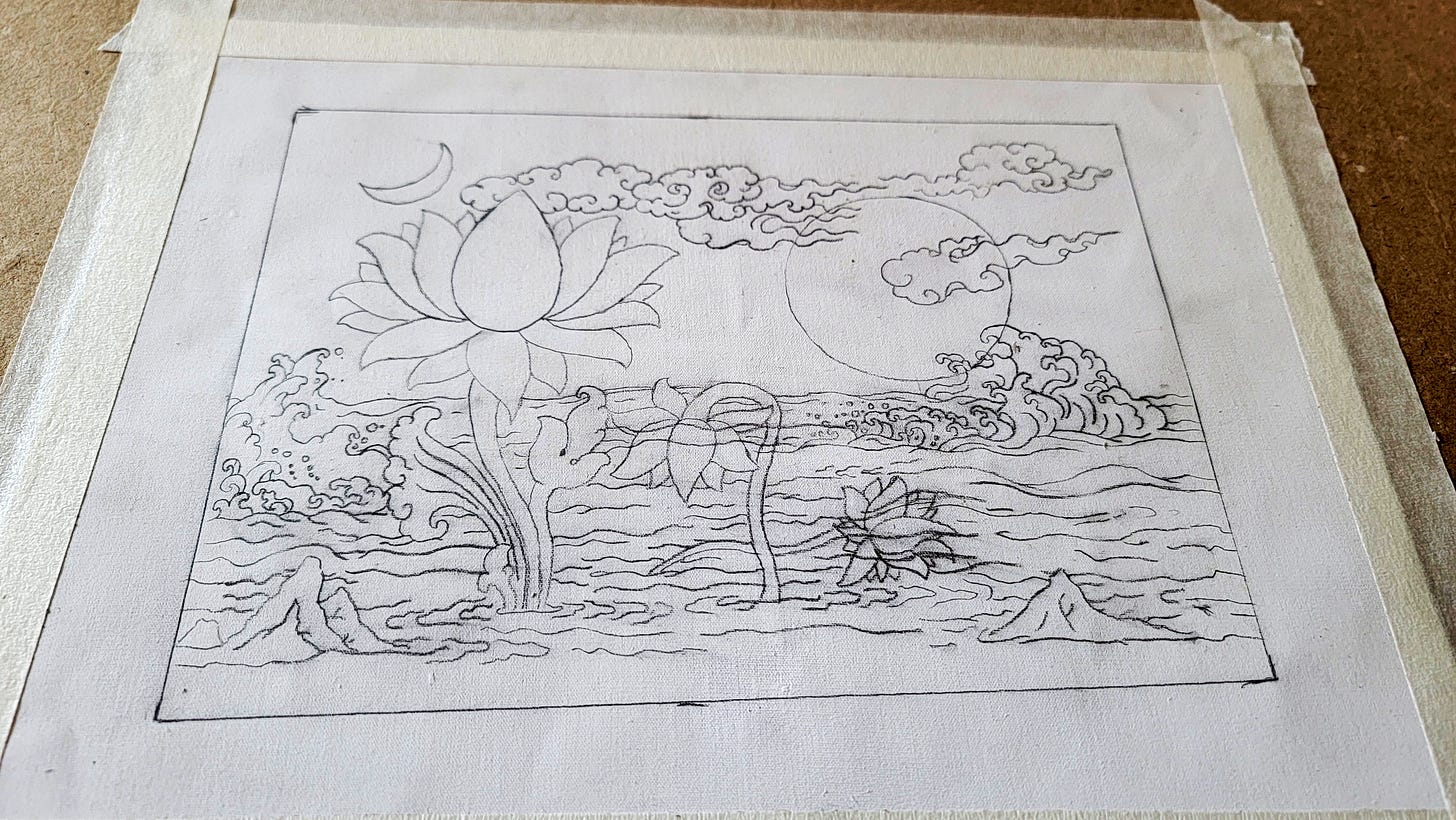

Much had been prepared for us in advance. A sketch had been worked out depicting a lotus flower ascending from the mud while two fellow flowers sink back toward it. It is a parable of some of us not being cut out for the work of enlightenment and falling toward worldly concerns though reality beckons.

Some kind soul transferred that drawing to canvas, which is primed with hide glue and white clay.

With that, we began painting. The method is to fill in areas of the drawing with color and then apply a dark outline. To say that this felt familiar would be an understatement. There is a bit of modeling in the form of a diluted version of the outline color laid next to it. I am stealing the hell out of that. A surprising amount of the picture is painted in a manner akin to a wet-into-wet watercolor technique—you lay down white, for instance, and noodle some indigo into it before it dries. This is the instructor’s demo.

Here is the view of the table after we had been working a while.

Works in progress by master and students were all over the studio. One was a four-foot-high Amitābha (I think) that gave Chritakar an opportunity to discuss the working properties of lapis. It doesn’t grind smooth or cover well, and it’s expensive, so we were using indigo, and painters usually start a blue area with indigo before glazing it with lapis.

Here’s a five-inch detail of another work in progress, at which Chitrakar dabbed while we worked.

The day was a delightful cross-cultural collision of art nerds. The atelier students were interested in the fact that I‘m an egg tempera painter and wanted to know about the commonalities, which are extensive. It’s intriguing to consider that at the time Botticelli was painting, Paubha artists were working out their tradition using the same materials, the most precious of which were sourced from the same mines in what we now call Afghanistan.

Painting is amazing.

Content at DMJ is free but paid subscribers keep it coming. They also have access to Dissident Muse Salons, discounts in the print shop, and Friend on the Road consultations. Please consider becoming one yourself and thank you for reading.

Our current title in the Asynchronous Studio Book Club is Art in America 1945-1970: Writings from the Age of Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and Minimalism by Jed Perl. For more information, see the ASBC homepage.

The current exhibition in the Dissident Museum is David Curcio: The Point of the Needle.

Amen to that. Painting is great! Thanks for the history lesson and the painting lesson. Funny how people see that deity as forbiddingly scary but i see them as whimsical. Cheers!

Yeah ~ Finally getting to WORK!

I love that they start you w/ coloring pages...

Gotta work up to those panoramic visions of apocalyptic reality.

🌼🖍🎨💙