Old Masters: A Comedy (1)

An Asynchronous Studio Book Club reading of Old Masters: A Comedy by Thomas Bernhard.

Are you enjoying your light summer read? (cough)

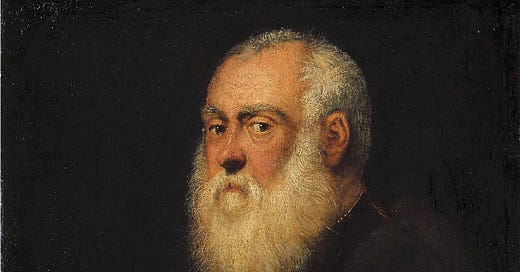

So far Old Masters has been eighty pages of unrelenting bitching. The narrator is one Atzbacher, about whom we know nothing except that he is obsessively recalling a conversation from the day before with another man, Reger, upon whom he is spying as the latter sits on a favorite settee at the Kunsthistoriches Museum in Vienna. Reger’s observations mix freely with Atzbacher’s, but both find nearly everything damnable. A third man, Irrsigler, guards the Bordone Room. Thanks to a bribe long ago he saves Reger’s spot for him, opposite Tintoretto’s Portrait of a Man with a White Beard. Reger describes Irrsigler as a dimwit mouthpiece. He indicates that his deceased wife used to serve the same purpose. Implicitly, Atzbacher has become one as well.

There’s no plot to speak of but the inner dialogue of Atzbacher is an amusing exposition of Reger’s character. Reger is a music critic, and a critic of the kind that I set out to avoid becoming—so overtaken with the critical mentality that it escapes its proper domain and extends to everything else, including the sunset. Well-done criticism regarding one’s subject of expertise is a noble craft. But for most of life, one ought to express gratitude that it’s happening and leave it at that.

When Reger, through Atzbacher’s recollection, describes the many imperfections in the paintings in the Kunsthistoriches, he’s making arguable points. By the time he’s describing their makers as “Religiously mendacious assistant decorators of the European Catholic rulers” (p. 48) he’s gone off the deep end. When he dismisses Heidegger as a “total spiritual wash-out” (p. 73) it’s hilarious. When he recollects painfully how his parents used to claim to be related to him, it is revealed that his problem with Heidegger is not contained to the philosopher’s work. By the time he growls “I hate the sun more than anything else in the world” (p. 78) he seems ghoulish.

Whether and to what degree Bernhard wants us to sympathize with this man is not yet clear. For two months in 2019 I lived in an apartment practically upstairs from the Leopold Museum when I did my Fulbright. Vienna is one of the most beautiful cities on earth. Weiners can often be heard complaining about it, and the country and its culture more broadly.1 I once went to a lecture and the artist delivering it announced that he would proceed in English because he did not care much for his “Nazi language.” I protested later, yours is the language of Rilke and Goethe and you need not feel this way. He smiled but remained unmoved.

Another time, I had a conversation with a hotelier that went something like this:

Me: I have a cultural question for you. I’m not the kind of ignorant American tourist who assumes that everyone on earth speaks English. So I begin conversations with Bitte, sprechen sie englisch? But when I do, people react as if I’ve asked them whether they’re retarded. “Yes, of course,” they reply, every time, in perfect English. Most of them know English better than a lot of Americans. What’s the right play here?

Hotelier: People in Vienna are going to be grumpy about it either way, so do whatever you prefer.

Austria is also in the habit of reviling its geniuses. The doctor to whom it first occurred that regular hand-washing would reduce the spread of infections was an obstetrician at Vienna General Hospital named Ignaz Semmelweis. He implemented hand disinfection as policy and mortality in his ward dropped from 18% to less than 2%. For publishing his findings, he was mocked and thrown into an asylum, where he died after being beaten by the guards. When a century and a half later Austria adopted anti-Covid measures so draconian and divorced from scientific reasoning that many of them were later declared unconstitutional, in certain respects it was true to form.

Weiners are conscious of their native stuffiness and tendency to bureaucratize themselves into disaster, but they’re mostly helpless to stop themselves. Mind you, I came to adore them and I’m still in touch with a few. Bernhard went the other way, descending into such loathing that his will forever forbade the publication or performance of his work in Austria. His literary executor flouted the ban a decade after the author’s death, which wasn’t long after Old Masters was published. Whether that defied the wishes of the deceased or belatedly gave the author his due—putting things right long after the fact is practically a national trait—is an open question.

In any case, I bought an annual pass to the Kunsthistoriches in 2019 and made it pay for itself in three weeks. So far I find the novel plausible and amusing. I spent enough time in the setting that the descriptions are bolstered by recollections, though they are happier and less fraught than the narrator’s.

Content at DMJ is free but paid subscriptions keep it coming. Please consider one for yourself and thank you for reading.

Our current title in the Asynchronous Studio Book Club is Old Masters: A Comedy by Thomas Bernhard. For more information, see the ASBC homepage.

Dissident Muse’s first publication, Backseat Driver by James Croak, is available now at Amazon.

Aphorisms for Artists: 100 Ways Toward Better Art by Walter Darby Bannard is out now at Allworth Press. More information is available at the site for the book. If you own it already, thank you; please consider reviewing the book at Amazon, B&N, or Goodreads.

Philadelphia, likewise, is loaded with people who criticize Philadelphia bitterly, yet refuse to leave. Vienna and Philadelphia are sister cities in that respect.

"Familiarity Breeds Content" by Joseph Epstein. I highly recommend this book of his essays.

Taking a pass on this book for another kind of summer read...