In 2005, Dushko Petrovich wrote this about Part IV of “Greater New York” at MoMA PS1:

Painting has been both dead and back for a little while now, and Greater New York is no exception. Painting hangs out with harsh videos, miniature amusement park rides, and big photos of failed politicians. When the artists resort to painting, they seem in particular to need its elevated discourse, its easy combinations of recognized languages, or, above all, its inherent stillness. Many of the paintings seem simply to wish not to keep going, which, if they were sentences or pop songs, would be expected of them. As it is, they can get away with a pose. Their audience, however, is less still and moves swiftly toward the café.

In August 2014, Jed Perl wrote an essay that appeared with a title not of his choosing, “Liberals Are Killing Art,” in which he noted, trenchantly:

The challenge for everybody who is involved with the arts—with opera, dance, and theater companies, museums, symphony orchestras, newspapers, magazines, and publishing houses—is how to make the case for the arts without condemning the arts to the hyphenated existence that violates their freestanding significance. There are surely reasons to link art to education, to tourism, to urban renewal, but all such efforts will be stop-gap measures, bound ultimately to fail, unless they are grounded in an insistence on the products of the imagination as having their own laws and logic. The friends of the arts are used to doing battle with budget cuts in the public and private sectors, with the audience’s ever shortening attention span, with the shrinkage of arts coverage in newspapers and magazines. But among the greatest enemies of the arts are the enemies that lie within, in the arts community’s seemingly liberal demand that all discourse be reasonable, disciplined, purposeful, useful.

In June 2015, William S. Smith wrote this about a talk on art criticism at the Superscript conference at the Walker Art Center:

Lack of diversity is often described as a part of a crisis of art criticism or a crisis in publishing. But I wonder if we should be asking if this is really a crisis for art. If the system is skewed in such a way that writers who are equipped to comment on diverse modes of cultural production have no investment in the visual arts and find the life of writing about it unsustainable, then the visual arts will no longer be a credible public forum for exchanging ideas. It will instead whither into an elite game, a subculture for elderly white people interested in private aesthetic experience and a narrow view of social prestige. In the long term, that hardly sounds like a sustainable business model for anyone.

A week later, Michael Lind excerpted the above paragraph from Petrovich in an essay in which he complained:

The process of escalating sensationalism ultimately reaches its reductio ad absurdum in any fashion-based industry. In the case of painting and sculpture the point of exhaustion was reached by the 1970s with Pop Art and minimalist art and earth art and conceptual art. Can a row of cars be art? Sure. Can an empty canvas be art? Sure. Does anybody care? No.

That’s why I want my money back.

The share of my college tuition that went to a few art history classes wouldn’t amount to much, even with interest. But the time I that wasted on studying what, in hindsight, was nothing more than a series of ephemeral stylistic fashions among rich people in the Paris and New York art worlds, of no lasting significance whatsoever, is time that I could have been devoted to subjects of real cultural importance to members of educated people in our own day and age.

One month after that, in July 2015, Michael Lewis described How Art Became Irrelevant:

Without a sincere concept of the meaning of civilization, one cannot explain why a masterpiece of Egyptian New Kingdom art counts for more than a creation of 1960s industrial design (other than in dollar value). If one cannot do even that, it is hard to see how one might set out to make serious and lasting art. To make such art—art that refracts the world back to people in some meaningful way, and that illuminates human nature with sympathy and insight—it is not necessary to be a religious believer. Michelangelo certainly was; Leonardo da Vinci certainly was not. But it is necessary to have some sort of larger system of belief, a larger structure of continuity that permits works of art to speak across time. Without such a belief system, all that one can hope for is short-term gain, in the coin of celebrity or notoriety, if not actual coins.

In September 2015, noting the trend from the prior year, and taking inspiration from Perl, I suggested that Democracy is Killing Art:

[W]e have to confront the possibility that an egalitarianism which accepts multiple systems of belief is incompatible with a sense of civilization—not as an abstraction, but as a particular belief system to which one can ascribe and thus belong. I am not talking about belonging to civilization, but belonging to a civilization. Equality, democracy, social or economic justice of the remedial varieties, relativism, inclusiveness, and participation ultimately contradict that larger structure of continuity. …

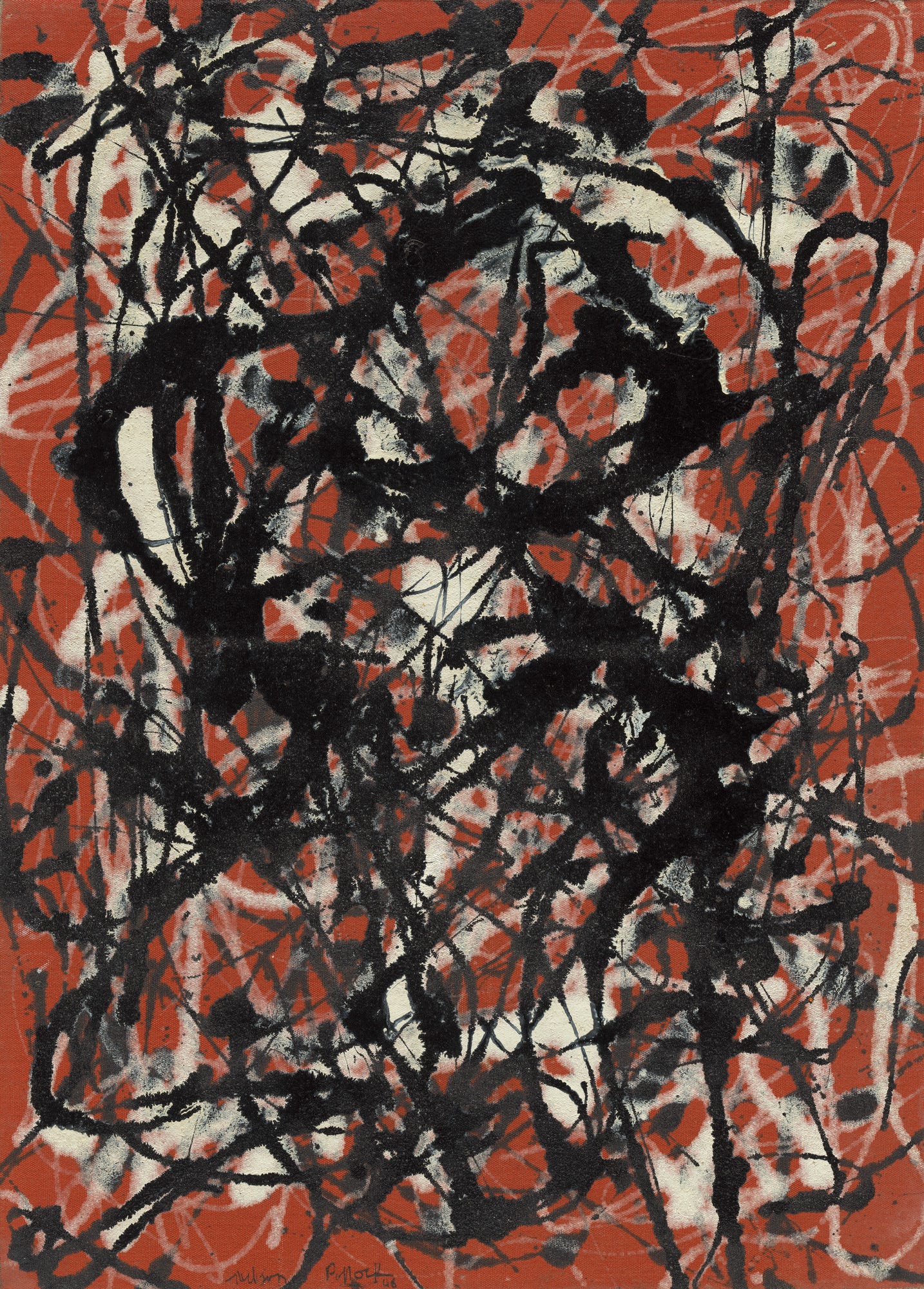

It may be that the ideal conditions for art are culturally homogenous, hierarchical, classist, territorially expansive, capitalist monarchies. … Excellent work was created earlier, but American art didn't ascend to worldwide triumph until after World War II, which produced an economic boom and the closest thing America ever saw to monarchic levels of nationalist pride. The high lasted from Pollock to Warhol. Then there was a proliferation of egalitarianism in the 1960s, and while civic good resulted, no artist ever again became a household name. As you would expect under egalitarianism, everyone went off to go work within his choice of belief system. Overarching artistic conventions began to be regarded with suspicion. Over the decades, audiences drifted off and gathered around mediums that celebrate their conventions, such as comics and long-form television. Art was left to flail.

This all returned to mind when in December 2024, Dean Kissick produced an essay with a terrifying opening—his mother was headed to the Barbican Art Gallery when a bus ran over her. She lost her legs. The stakes of life and art were thrown into sharp relief, and Kissick concluded that art had forfeited its moxie compared to 2014.

Only ten years ago, the art world was something very different: a globalized circuit of biennials and fairs that ran on the international trade of ideas and commodities. It was a space of spectacle and innovation, where artists tried out wildly different mediums and entertained radical ideas about what art could do and why. They were workshopping new cultural forms for a new millennium. Art was where experimentation happened, where people worked out what it felt like to be alive in this strange new century and how to give that feeling a form. Artists were researchers who were never expected to come to any conclusions. They had the freedom of absolute purposelessness.

And now?

But as faith in the liberal order began to fall apart around 2016, this conception of art no longer seemed relevant. As concerns over identity, social issues, and inequalities intensified, there was a sense that the art world had grown frivolous and decadent, that the proliferation of forms and approaches over the decades had reached its limit. Art, which had previously been a way to produce discursive polyphony, aligned itself with the dominant social-justice discourses of the day, with works dressed up as protest and contextualized according to decolonial or queer theory, driven by a singular focus on identity.

My first reaction to this was, Welcome to the club. I wrote my 1994 graduate thesis in Ogden Nash-style rhymed couplets. The opening stanza sang:

In the age of the photographed and video-recorded The function of art has waxed distorted: Conceptual diagrams and dirt on the floor, Political statements proclaimed by the score. Give me the old days, though past and quaint, When writers used writing and painters used paint, When activism, graffiti and multiculturalist grumbles Could be distinguished from art, and not in a jumbles, When talent and craft were the things of import, Instead of connections with a bar in New York. Appropriation and forced social relevance: I wouldn't mind seeing it all trampled by elephants.

Having found such tendencies unsatisfactory for three decades, my second reaction to Kissick’s observations, such as these…

This turn was a consequence of the art world’s own exhaustion and overexpansion; here was a new direction for art, a belief system to follow that might restore some of its meaning and relevance, perhaps even a grand narrative and a purpose. The ambition to explore every facet of the present was quickly replaced by a devout commitment to questions of equity and accountability. There was a new answer to the question of what art should do: it should amplify the voices of the historically marginalized. What it shouldn’t do, it seemed, is be inventive or interesting.

…was, when I say things like that, it’s a day ending in Y. But maybe people will heed this young fellow who traveled in the circle of Hans Obrist and thrilled at Paola Pivi when she “filled a Swiss Kunsthalle with three thousand cups of cappuccino and a leopard” back in the heady twenty-teens. I remember the time differently. Certainly, “faith in the liberal order began to fall apart,” but the result wasn’t only that art “aligned itself with the dominant social-justice discourses of the day.” Those discourses took a viciously accusatory turn that has culminated in an effort to rid the art world of Jews.1 The tone is only now starting to quiesce because Trump was re-elected and history has done to progressive narratives what that bus did to poor Mrs. Kissick.

Kissick’s essay shares much in common with Perl’s from 2014. If you find the former convincing, consider reading Perl’s Authority and Freedom from 2022, which I reviewed for Quillette. Kissick wants artists to have “the freedom of absolute purposelessness.” Perl wants “to release art from the stranglehold of relevance.” Kissick is pleading for the autonomy of art, just as Perl has been petitioning expressly for much of his later career. From Authority and Freedom:

The novelist and short story writer Flannery O’Connor made a case for the singularity of the creative act in a letter she wrote to a friend, Father James McCown, in 1956. The subject was a work of fiction that O’Connor didn’t like at all, although her friend apparently imagined that as a serious Catholic she would find its moral appealing. O’Connor explained to McCown that the book “is just propaganda and its being propaganda for the side of the angels only makes it worse. The novel is an art form and when you use it for anything other than art, you pervert it.” She went on to say that “art is wholly concerned with the good of that which is made; it has no utilitarian end. If you do manage to use it successfully for social, religious, or other purposes, it is because you make it art first.” O’Connor’s statement deserves to be underlined: “You make it art first.” She didn’t leave it at that. “You don’t dream up a form and put the truth in it,” she argued around the same time. “The truth creates its own form. Form is necessity in the work of art.” We might expect to hear an abstract painter say something like this. O’Connor’s insistence on the autonomy of art is all the more remarkable because it comes from a writer who produced not brilliant wordplay but unsparing studies of the human condition. Perhaps only a formalist could have seen the savagery of her contemporaries with as much clarity as O’Connor. “Vocation implies limitation,” she wrote in 1957, “but few people realize it who don’t actually practice an art.”

This is not adequately understood: The autonomy of art does not preclude the political or moral spheres, it subordinates them. When it’s the other way around, the ensuing expression is propaganda by definition. J.F. Martel characterizes propaganda as pornography in a minor key. It is a vulgar exercise. Neither Perl nor Kissick claims that art must not deal with politics, morality, identity, or theory. They are asking for art to be art first.

This seemingly innocuous demand causes extreme agitation among people who defend the primacy of politics in art or view art as a byproduct of political history. Perl’s treatise from 2014 was not well received. Mostafa Heddaya dismissed it:

Like much of his criticism, Perl here seems to be talking to no one in particular, bellowing at the present from an oblique angle. And for someone drawing from the ambered debates of modernism, it seems deeply strange for him to blindly assert that emotions are not political, or that politics cannot be emotional.

Perl didn’t assert anything of the kind, blindly or otherwise. This is Hyperallergic, so expectedly dishonest and stupid.2 Nevertheless, it was expressed before the Vicious Turn of the mid-twenty-teens. In contrast, here’s Christian Viveros-Fauné on Kissick.

If curmudgeonly oracles like [Robert] Hughes no longer boast prominent tribunes — he spent more than three decades writing weekly art criticism for Time magazine — the public commons is awash with non-experts with YouTube-ready answers for legions of “This-explains-everything-addicts.” They include populist podcasters, wellness gurus, corporate “thought leaders” and outright flimflammers — crisis-borne confidence characters of the sort W.B. Yeats once pegged as “full of passionate intensity.” Enter, stage Right, a youngish, German-born, UK-raised art and fashion writer named Dean Kissick. A self-appointed slayer of woke mobs and defender of the icky 1970s Viennese Actionists (think, naked white guys on crucifixes smeared in animal guts), he arrives just in time to enact yet another Groundhog Day reprise in the pages of last month’s Harper’s: a bougie millennial parroting of novelist Tom Wolfe’s cavil from half a century ago.

The essay is a shotgun blast of unenlightening invective.

Titled “The Painted Protest: How Politics Destroyed Contemporary Art” — the tip of the retro fedora is to The Painted Word, Wolfe’s caricature of 1970s conceptual art, first excerpted in the pages of the same magazine in 1975 — Kissick’s much-commented-upon, scorched-earth denunciation of art circa 2024 managed an unlikely feat. It parodied contemporary art’s sanctimonious “social turn,” called out absurdities at marquee museum and biennial exhibitions, and dutifully red-Sharpied the “fantasies of resistance” attendant to the art world’s “liberal orthodoxy and feel-good ambient diversity.” What the essay did not do is equally crucial: It failed to acknowledge great works of political art from Goya to today — Kerry James Marshall anyone? Hans Haacke? Nan Goldin? — in order to paint the field of contemporary art as a dishonest comedy of manners à la Wolfe.

By the time Viveros-Fauné’s spleen was fully vented, he had charged Kissick with white privilege twice. Recognition that Kissick’s mother is Asian didn’t slow him down. Heddaya accused Perl in 2014 of “drawing from the ambered debates of modernism.” Viveros-Fauné also invoked amber as he concluded regarding Kissick:

In our time, as during previous crises, the Kissick style of alarmist writing amounts to criticism as conspiracy theory. It’s not new, and it’s hardly radical. No matter how much Kissick (or Wolfe’s ghost) spins the hateful crackle of America’s ambient static, the coming culture wars will need more and better political art, not less. Fixing white privilege like angry wasps in amber and dialing the clock back won’t take the politics out of culture — or make art or writing great again.

“Hateful crackle”! For the crime of suggesting that artists not feel obliged to spout rote political tropes.

Saul Ostrow likewise took Kissick to task for failing to recapitulate a history of political art that was not germane to Kissick’s point. Haacke came up again.

In particular, he does not take note of influential political artists such as Hans Haacke or the Feminist and Black Arts Movements of the 1970s. He neglects several critical aspects of the contemporary art world, such as art market and art institutions’ bias towards what some would consider “failed” political art, like that of Jenny Holzer and Judy Chicago, that is politically engaged but may lack aesthetic power. Nor does he address the preferences of museums and major galleries for work, like Simone Leigh’s or Theaster Gates’s, that is provocative enough to stimulate political discourse but not so radical as to threaten stakeholders’ interests. These dynamics elevate a certain kind of politically-themed art while suppressing work that might drive real political change, leaving truly radical artists bereft of financial support and venues and limiting their visibility and impact. In sum, Kissick does not provide a comprehensive analysis of the relationships governing cultural production and its distribution in the contemporary art world.

I pointed out in the comments section that Kissick was comparing the art of the present unfavorably to that of ten years ago, not fifty. Why does that cause anyone to cough “Haacke!” like they’re bringing up a hairball? Kissick did not claim that no political art has ever been effective and that none is now. He cited some in three long paragraphs that began, “Despite my jaundiced view of contemporary art, I do still encounter works that take me right out of the world.”

That seemed lost on Martin Herbert.

Let’s move quickly past, but not ignore, the author’s documented proximity to the performatively/not-performatively anti-woke Dimes Square crowd in New York City – which can’t easily be separated from his disinterest in art rooted in identity politics – and alight on him noting, earlyish in his essay, that ‘Throughout my twenties… art felt very important’. He goes on to reminisce about being young and glamorous and free in the post-2008, post-Internet artworld. But then, by 2017, as that trend is dying from overexposure and as social justice movements are simultaneously gathering steam worldwide, artists from the global south and Indigenous artists and Black artists and more women are starting to be given voice. For Kissick, it’s initially exhilarating to see all this different art patchworked together. But then it becomes biennale orthodoxy and virtue-signaling and monotony. Suddenly, somehow art’s not fun or challenging or even interesting anymore.

Herbert’s thesis is that nothing has gone wrong with art, Kissick is just getting old. Viveros-Fauné also noted resentfully that Kissick “briefly chronicled and participated in a weirdly retro, lily-white, pandemic-era, Manhattan art scene called Dimes Square.” When Herbert wrote that “contemporary art comes with the provocative bonus that if you criticize it, you’re implicitly racist and/or sexist,” it wasn’t clear whether he was being ironic. Viveros-Fauné makes me suspect that he wasn’t.

I thought Kissick’s essay was benign and slightly spicy. It didn’t introduce any observations or critiques I haven’t seen in some form since I got out of graduate school, but the conclusions are lovely and true: “I don’t particularly care to have my awareness raised; I’d rather view art that tears open my consciousness, that opens portals into the mysterious.” Perhaps a certain kind of awareness had fallen on a series of writers ready to receive it, from Greatest Generation Clement Greenberg to Silent Generation Walter Darby Bannard to Boomer Jed Perl to Gen X Yours Truly to Millennial Dean Kissick, and would likely tick on through the generations thereafter, inspiring people to ask art to be art first.

The essay should not have prompted critics to have a litter of kittens. That is more interesting than the essay itself.

Two summers ago I characterized our current moment as postcritical.

Criticism will continue to be written in the postcritical era just as art continues to be made after Danto’s end of art. But one, following art’s example with respect to the philosophical turn, henceforth it will be written in light of its exogenous marginalization by big art world money and its endogenous marginalization by postliberal progressive politics. Two, the system is closed and the energy is running out. Criticism’s chief concern will be the policing of opinion, from which not even the Seph Rodneys of the world will be excused.

Viveros-Fauné, Ostrow, and Herbert are policing Kissick’s opinions. They would not have felt that necessary unless they perceived Kissick as having walked up and kicked their cop car.

Here’s a hypothesis. In 1925, Alfred Stieglitz started showing Demuth, Dove, Hartley, and Marin at Intimate Gallery. High modernism clicked on in 1946 when Pollock painted Free Form. High postmodernism started when Duchamp commissioned new versions of Fountain (originally 1917) in 1964. The high post-historical period began in 1984 with the publication of Arthur Danto’s “The End of Art.” The postcritical era began in 2002 with the advent of Art Basel Miami Beach. It’s now 2025, and we’re nearing, maybe past, the end of the roughly two-decade lifespan that art historical movements of the last century have endured. Postcriticality is dying. Gainsaying of postcriticality that could have been dismissed ten years ago must be answered.

When Kissick kicked the cop car, its headlights came on and the radiator hissed angry steam. Onlookers laughed. No wonder Viveros-Fauné is upset.

What’s next? We will find out any day now.

Content at DMJ is free but paid subscribers have access to Dissident Muse Salons, print shop discounts, and Friend on the Road consultations. Please consider one for yourself and thank you for reading.

The current exhibition in the Dissident Museum is David Curcio: The Point of the Needle.

I predicted in June 2023 that the “Foreigners Everywhere” theme of the 2024 Venice Biennale, with its emphasis on “artists who are themselves foreigners, immigrants, expatriates, diasporic, émigrés, exiled, and refugees,” would not include the Jews. As this article reports, the German pavilion featured Israeli artist Yael Bertana. People reacted to that with disgust.

I left a comment on that post: “Perl did something interesting here, accurately noting a utilitarian and politicized tendency within rationalist liberalism that is hostile to the core project of art, and he did so from within liberalism in an act of honest introspection. I knew that tribal liberals, as opposed to the principled ones, would react badly to it, but I didn’t think that they were going to be this petty about it.”

Having just read the Kissick article, I'm somewhat (not?) surprised by the wider response. His critique is of the mildest sort. Fascinatingly, the art world of his youth that he mourns for is one that I thought (at the time and still do) was utter garbage. He seems trapped in the "novelty as progress" or "novelty as goodness" narrative that defines the way Western art history has been contextualized since modernism.

The hyper-identity art of today elicits little more than yawns of indifference from me, and I mostly avoid writing about it for fear of being accused of sexism, bigotry or ___phobia. But the identity-art style-checking that Kissick finds so unimaginative and symptomatic of art's decline has, in many cases, yielded a level of formal and technical excellence in contemporary painting that was completely absent from the art of his miraculum decennium.

GOOD. May the postcritical era in the arts die.