I Paint What I Want to See (2)

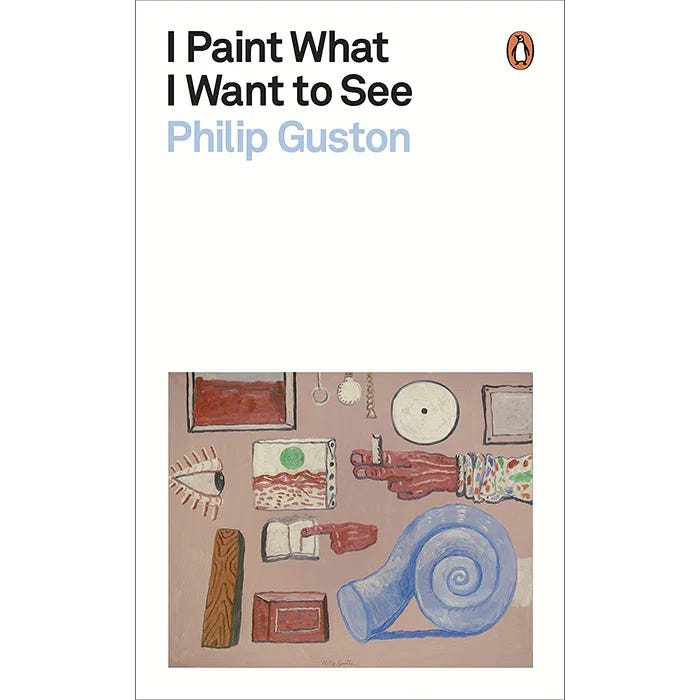

An Asynchronous Studio Book Club reading of I Paint What I Want to See by Philip Guston.

Last night I had a conversation with a fellow artist who teaches at a university in Massachusetts. He described a problem I hear about more and more often from teaching artists: he asks art students which artists they’re looking at for inspiration, and the answer is no one. I gave up on trying to land adjunct gigs in 2018 but even then it had become apparent that student quality was in a permanent and dire decline. There were always a few live ones—the kids to whom you’re really teaching the class—but the baseline around them evinced increasing dysfunction. I sincerely tried to help everyone, aware that the education system from which they emerged was likewise in permanent and dire decline, including the one in which I was teaching. I had to assume that I was somehow part of the decline. It’s easy to disdain your times; it’s impossible not to be a part of them.

The indifference wasn’t news, but it struck me anew for having reread the talk that Philip Guston gave to the Yale Summer School of Music and Art 1974, recorded in I Paint What I Want to See.1 Genesis 6:4, “The giants were on earth in those days.” Had Guston walked into my last university classes and dispensed art wisdom, it would have been like a lecture about linear algebra delivered to guinea pigs. Granted I wasn’t teaching at Yale. But I doubt that even Yale has escaped either student or institutional decline in the intervening fifty years, particularly in light of revelations that nearly every Yalie is an A student, suggesting that grades there have gone the way of the Zimbabwean dollar.

Likewise goes for the “Conversation with Clark Coolidge” (p. 111), captured on Coolidge’s tape recorder in 1972. After studying it again I texted another art friend, “Do these kinds of conversations happen anymore? Obviously not here in the woods, but anywhere?” She answered, “We could.” That’s the kind of art friend you treasure. Page 141:

PG: There’s no movement to speak of, visually. It’s just there, and yet it’s shaking, like throbbing, or burning or moving, but there’s no sign of its moving. Now that book, I may be reading my things into it that other people don’t see, but I don’t think so.

CC: No, I see what you mean. It’s vibrating.

PG: It vibrates! In other words, it’s like nailing down a butterfly but the damn thing is still moving around. And this seems to be the whole act of art anyway, to nail it down for a minute but not kill it.

This passage on pages 152-153 is Mametesque:

PG: Yeah, I mean partially open space, that’s right. You mean, it’s defined as to where it’s going to go, that one line?

CC: Well, it’s just breaking loose, too.

PG: Breaking loose.

CC: You got it at the moment of detachment.

PG: That’s right. Exactly. It’s like in physics, an elaborate concept could be contained in a simple symbol, you know?

CC: Yeah.

PG: That’s like a symbol of a very elaborate system there.

CC: Like an infinity sign.

PG: Exactly.

CC: It’s ridiculous.

PG: Exactly. Exactly.

CC: I mean, there’s something endlessly…

PG: Which has to do with that area being open all around.

CC: It’s just an endless action.

PG: That’s right.

CC: Because it never stops.

PG: It keeps renewing itself. But then, you see, that same phenomenon can happen with a more tangible…

CC: Ah!

PG: …form.

Those exchanges are probably nonsensical to most readers. I only understood them because I’ve had conversations much like them with a handful of good artists over the years. One day I visited a friend in his studio, and he held up a monograph of Sickert and said, “Fuck!” I answered, “I know.” I don’t mean to present myself as a mystic, but it was like Mahākāśyapa smiling at the upheld flower. Nothing more needed to be said. It can be like that among friends who see deeply.

That conversation contrasts with the later one with Harold Rosenberg (p. 219), who could see deeply, but he often got ahead of himself. Guston had to correct him.

PG: Some months ago, a university here asked me to come and give a slide talk on my work, saying that the faculty and students would be most interested in hearing me explain why and how I moved from abstract painting to figurative painting. I declined and giggled to myself when I read the letter, because in the late forties and early fifties I would get invitations to come and give a slide talk and explain why and how I changed from figurative to abstract painting. So you can’t win. I mean, it’s impossible to explain.

HR: You can’t win, but you can keep on talking.

PG: No, you can keep on painting.

The last chapter collects studio notes from Guston’s last decade. There are gems within. Page 244:

Pictures should tell stories. It is what makes me want to paint. To see, in a painting, what one has always wanted to see, but hasn’t, until now. For the first time.

On page 249, one last expansion upon the Generous Law discussed last week:

The Laws of Art are generous laws. They are not definable because they are not fixed. These Laws are revealed to the Artist during creation and cannot be given to him. They are not knowable. A work cannot begin with these Laws as in a diagram.

They can only be sensed as the work unfolds. When the forms and spaces move toward their destined positions, the artist is then permitted to become a victim of these Laws, the prepared and innocent accomplice for the completion of the work.

His mind and spirit, his eyes, have matured and changed to a degree where knowing and not knowing become a single act.

It is as if these Governing Laws of Art manifest themselves through him.

On page 256, in a charming story about the travails of Philip the Painter and Philip the Writer, who wanted to meet but couldn’t negotiate a relationship with the terrible power of the telephone:

Through a new source of willpower, Philip the Painter overcame his nervousness and was calm as he prepared to entertain his friend, Philip the Writer. This determination was accomplished by the feeling of security that they would spend their evening, during and after dinner, leisurely discussing their mutual nervousness about the time stolen from their work by the world outside. He knew they would exchange their fears of the ringing telephone. Philip the Painter knew that he and Philip the Writer would speak of their miseries and would plan strategies to prevent the frightening theft of time.

With that, I have a canvas waiting for me in the studio. Thank you for reading along.

Readers have already made moving comments about the book in last week’s post, but feel free to add any additional below. Next Friday the Asynchronous Studio Book Club will cover Part I of Aesthetics of the Familiar: Everyday Life and World-Making by Yuriko Saito.

Content at DMJ is free but paid subscriptions keep it coming. Please consider one for yourself and thank you for reading.

Our next book for the Asynchronous Studio Book Club is Aesthetics of the Familiar: Everyday Life and World-Making by Yuriko Saito. Obtain your copy and jump in. For more information see the ASBC schedule.

Dissident Muse’s first publication, Backseat Driver by James Croak, is available now at Amazon.

Aphorisms for Artists: 100 Ways Toward Better Art by Walter Darby Bannard is out now at Allworth Press. More information is available at the site for the book. If you own it already, thank you; please consider reviewing the book at Amazon, B&N, or Goodreads.

Since just last week, this book has been noted as “sold out” at the publisher and has gone up in price by $3 at Amazon. You might want to get a copy soon if you’re still thinking about it.

The use and abuse of art

Barzun, 1972

MFA 1976

This little book gave me a concussion.

Dazed and confused ever since

Thought provoking and a fun ride with you and Philip and your readers. Keep it moving.