Abstraction and Empathy (1, second attempt)

An Asynchronous Studio Book Club reading of Abstraction and Empathy: A Contribution to the Psychology of Style by Wilhelm Worringer.

I cried for help, and help came. Michael Schreyach (author of ASBC book Totality) sent in a 1967 essay by Rudolf Arnheim titled simply “Wilhelm Worringer on Abstraction and Empathy.” The analysis clarified why I was having so much difficulty with the title in question. Worringer’s central argument is straightforward but embedded in supporting claims broader than can be comfortably justified. (It also reads like a German doctoral thesis from 1906, which of course it was.)

The central argument asserts two poles of art-making. One of them is a will to naturalism, the other a will to abstraction. The former he calls empathy because it is the psychological or spiritual insertion of the artist’s presence into objects as fellow sensuous beings, in a spirit of joyful confidence about his place in the world.1 Abstraction, in contrast, is the product of anxiety, reflecting a view of the world conjured into existence by magic, inscrutable regarding its workings, and unamenable to reasoning. The former tendency is exemplified by mimetic Greek art, the latter by stylized Egyptian art. Arnheim, conceding its truth in great measure, quotes the diary of Paul Klee from 1915: “ The more terrifying this world (precisely as today), the more abstract its art, whereas a happy world brings forth an art of the here and now.”

This argument represented a sharp break from prior attitudes among art historians. The dogma of the time held that antique and Renaissance efforts to render nature represented a paragon to which the work of all other people and times ought to be compared. Worringer condemned this as “European-Classical prejudice” (p. xiv). It rendered all that other art unintelligible. The notion is now commonplace in decolonial art history, but it was articulated by a German in 1906.

Changes in art-making are not so much a matter of varying ability, as one might conclude from the attitude that naturalism is the singular basis of comparison, but volition. Page 9:

The new approach, on the contrary, regards the history of the evolution of art as a history of volition, proceeding from the psychological pre-assumption that ability is only a secondary consequence of volition. The stylistic peculiarities of past epochs, are, therefore, not to be explained by lack of ability, but by a differently directed volition.

Without recognizing that each age and people has its own volition, one remains at the mercy of “the inertia that prevents our spirits from leaving the so narrow and circumscribed orbit of our ideas and from recognizing the possibility of other presuppositions. Thus we forever see the ages as they appear mirrored in our own spirits” (p. 11). No wonder the decolonial art historians don’t credit him. Practically all they do is project their tendentious presentism. Reading Worringer makes clear that this only compounds a mistake.

On page 13 he claims that what we call beauty in art is its power to bestow happiness, which is causally connected to beholders’ and creators’ psychic needs. “Thus the ‘absolute artistic volition’ is the gauge for the quality of these psychic needs.” Hammering nails into the coffin of the old approach, he declares:

Every style represented the maximum bestowal of happiness for the humanity that created it. This must become the supreme dogma of all objective consideration of the history of art.

Abstracting Egyptians regarded the world with terror. Oriental cultures more broadly, claimed Worringer, embraced abstraction out of philosophical or temperamental disdain. Page 16:

The civilized peoples of the East, whose more profound world-instinct opposed development in a rationalistic direction and who say in the world nothing by that shimmering veil of Maya, they alone remained conscious of the unfathomable enablement of all the phenomena of life, and all the intellectual mastery of the world-picture could not deceive them as to this. Their spiritual dread of space, their instinct for the relativity of all that is, did not stand, as with primitive peoples, before cognition, but above cognition.

This is where the argument started to go off the rails for me. The artists of the Buddhist world had a dread of space? Are you kidding me?

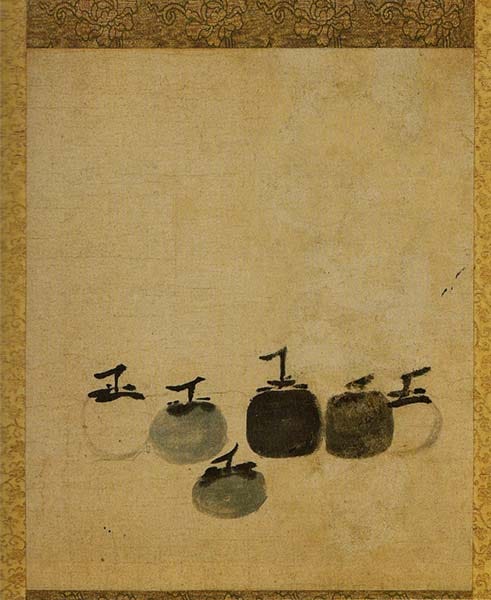

That is either a shortcoming in the thesis or a failure of terminology. Space, for Worringer, is a potential source of terror because we live in a world of three dimensions. The word irrefragable comes up in this book with surprising frequency. If one’s orientation to that world is essentially anxious, then abstraction seeks to abstract away that all-permeating depth and its necessary separations. Form in that case must be freed from space. “Space,” he says on page 22, “is the one thing it is impossible to individualize.” On the next page he quotes Adolf Hildebrand: “As long as a sculptural figure makes a primarily cubic impression on the spectator it is still in the initial stage of its artistic configuration; only when it has a flat appearance, although it is cubic, has it acquired artistic form.” Extrapolating, the exquisitely untouched expanses in Asian painting are abstraction, even if we would conventionally refer to them as space. The will to push form down to two-dimensionality is abstraction as well, seeking the kind of artistic form described by Hildebrand.

Arnheim was rather unimpressed with this characterization of abstraction:

In regard to the Orientals, who are Worringer's prime example of spiritual withdrawal from the irrational confusion of life, we shall only note that the first and most important of the six canons constituting the doctrine of Chinese painting ever since Hsieh Ho formulated them about 500 A.D. was the “Ch’i yun sheng tung,” the “Spirit Resonance (or Vibration of Vitality) and Life Movement,” a quality of the brushstroke by which the Breath of Heaven “stirs all of nature to life and sustains the eternal processes of movement and change… if a work of art has Ch’i it inevitably reflects a vitality of spirit that is the essence of life itself.” As to modern art, we may mention that for the most geometrical of Abstractionists, Piet Mondrian, a work of art was “art” only “in so far as it establishes life in its unchangeable aspect: as pure vitality.”

Later, Worringer makes distinctions between imitation and naturalism that Arnheim didn’t think are sustainable, at least not to that degree. Pages 27-28:

[Naturalism is an] approximation to the organic and the true to life, but not because the artist desired to depict a natural object true to life in its corporeality, not because he desired to give the illusion of a living object, but because the feeling for the beauty of organic form that is true to life had been aroused and because the artist desired to give satisfaction to this feeling, which dominated the absolute artistic volition. It was the happiness of the organically alive, not that of truth to life, which was striven after.

That nevertheless conveys why so much contemporary realist art is so ineffective, a deficit of feeling behind the volition. This, more generally, is how I’m finding the book valuable, not so much as a system (the possibility of which Worringer disdains anyway, on page 34), but as a forceful act of discernment in defiance of the bromides of one’s time. That is worth doing, perennially, so long as the resulting insights are worth preserving. In Worringer’s case they have proven themselves assuredly.

Content at DMJ is free but paid subscriptions keep it coming. Please consider one for yourself and thank you for reading.

Our current title in the Asynchronous Studio Book Club is Abstraction and Empathy: A Contribution to the Psychology of Style by Wilhelm Worringer. For more information, see the ASBC homepage.

“Franklin Einspruch: Tangibilia” is an online exhibition representing the physical one in New York in June 2024.

Dissident Muse’s first publication, Backseat Driver by James Croak, is available now at Amazon.

Aphorisms for Artists: 100 Ways Toward Better Art by Walter Darby Bannard is out now at Allworth Press. More information is available at the site for the book. If you own it already, thank you; please consider reviewing the book at Amazon, B&N, or Goodreads.

This takes on a more emphatic cast in German. Einfühlung (empathy) is literally “one-feeling.”

In The Comics, we use Space as a Time element, too. There is no eternity, only the eternal present experience of reading, that is to say, moving through space, motivation, pure vitality.

Is that abstraction, or is it dreadfully concrete?

Abstraction and Empathy is a dense, heavy read, one that requires rereading and clarification. Not your typical summer reading.

In the section “Naturalism and Style” (page 44), Worringer states:“The primal artistic impulse has nothing to do with the rendering of nature. It seeks after pure abstraction as the only possibility of repose within the confusion and obscurity of the world-picture, and creates out of itself, with instinctive necessity, geometric abstraction. It is the consummate expression, and the only expression of which man can conceive, of emancipation from all the contingency and temporality of the world-picture.” Wow, this is quite a statement. If I understand the above passage correctly, art created since 1900 is steeped in rendering nature. Perhaps I am missing something.