Totality (4)

An Asynchronous Studio Book Club reading of Totality: Abstraction and Meaning in the Art of Barnett Newman by Michael Schreyach.

Due to the excitement this week I gave myself permission to put down my yellow pad and pen and read Chapter 4 of Totality as a reader rather than a writer. This review is going to be breezier than previous installments, but there was still much to be had.

At this point Schreyach has established that the room in which a Newman is hung is as much a component of the painting as the acrylic or the canvas. The quote from Newman on page 125 is striking: “Is space where the orifices are in the faces of people talking to each other, or is it not between the glance of their eyes as they respond to each other?” Schreyach subsequently cites the film theory of Christian Metz to describe the effect of the painting as a relationship of enunciator and addressee, again invoking deixis. Don’t try this at home, kids—Schreyach is a trained professional on a closed, eight-foot-by-inch-and-a-half racetrack, the dimensions of Newman’s The Wild from 1950.

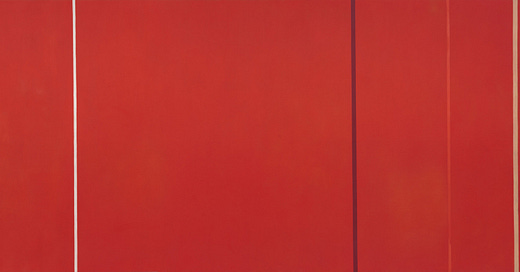

But just when it seems like it may be possible to view Newman, in working the extremes of scale ranging from the aggressive verticals like The Wild to the veritable murals like Vir Heroicus Sublimis (1950, 1951), as a precursor to environmental or installation art, Schreyach kicks over the relationship on page 141:

…Newman mobilized the medium’s traditional resources to represent an abstract yet controlled space of a thoroughly pictorial nature. Vir Heroicus Sublimis confronts actual space with a unique image and idea of nondimensional virtual space. And that might be tantamount to claiming that the painting is a critique of “the environmental” as such.

Schreyach drills down in the attached note:

Newman’s painting is not conveniently an occasion for viewers’ literal experiences of wherever they happen to be located, but rather communicates a specific idea about the difference between the painting’s projected space and the real space within which they encounter the work. That is why, although the visual and kinesthetic dynamics evoked by the image might make us more perspicacious about the painting’s structure of beholding, its meaning is independent of and irreducible to them.

Along the way we learn that Newman had interviewed Thomas Hart Benton. Footnote 48 on page 254:

The occasion was Newman’s failure to pass the exam for high school art teachers conducted by the New York City Board of Examiners. To protest what he took to be a biased exam, Newman organized the Fine Arts Substitutes Association and persuaded Benton to comment on the deficiencies of the test. A notice of the muralist’s negative verdict appeared in the New York Times…

Can you imagine some panel of nobodies deciding that Barnett Newman didn’t have the chops to teach high schoolers? I admit that I’m not terribly patient with bureaucracies in general, but dear Lord.

Schreyach’s three-stage analysis of Vir Heroicus Sublimis on page 152, I’m suspecting in advance, is the heart of the entire book. There he identifies, one, a demand for the viewer to find her best-suited physical position for viewing the work, which is close enough to evoke a sense of absorption into the field of color. (Use of the feminine form as a general pronoun usually annoys me, but by consistently referring to the viewer as she Schreyach can more easily distinguish whether he’s talking about Newman or the viewer. It’s a really smart literary choice.) Two, the breakages in the field halt a dispersion of the viewer’s self into the work. Third, the zips act to send the viewer’s attention upward, cathedral-like, into an awareness of the space around her.

In making those distinctions, Schreyach is able to contradict a critical tendency to lock up on the first stage, drowning in a lake of color and proceeding no further. It came up often enough to bemuse Newman (page 153):

I hope my painting has the impact of giving someone, as it did me, the feeling of his own totality, of his own separateness, of his own individuality, and at the same time of his connection to others, who are also separate. And this problem of our being involved in the sense of self which also move in relation to other selves… the disdain for the self is something I don’t quite understand.

This reminded me of something I had written in The Postcritical Era:

The shared valuation that went on in the aforementioned Vasarian narrative may be unavailable today, but there’s an opportunity for a renewed individualism which recognizes that our responses to art are at once personal and communicable via humanity itself. We need not be the solipsistic consumers of laissez-faire aesthetics, scratching private artistic itches by trading money for art objects. Most certainly we are not the mutually inscrutable silos of identity that contemporary politics would have us imagine ourselves. Rather we are owners of our own persons and borrowers of the common nature from which we derive our being. The force of art lives in both aspects of ourselves, spanning them, at once affording individual delight and connection to a greater sphere of life.

When Christa Noel Robbins and her kind try to assassinate Michael Fried and modernism more broadly for the aggressively cliched complaint of it being too pale, male, and stale, one might as well chalk it up to terminal conformity. But the deeper problem may be existential. In the space of a hundred years we’ve gone from a vital, individualistic avant-garde to a Stalinistic attitude that art has to serve the cause of social justice in some manner to be deemed important. From that vantage, Newman seems to be at a midpoint of a waxing societal desire, at least in the arts, to melt the self into the collective.

That people would still feel annoyance at abstract painting in 2024 is profoundly odd, unless, in spite of itself, its ethos of individualism—the need for a distinct sense of self to fully comprehend it—is thwarting powerful political interests. That appears to be the case. Masking for Covid turned out to be worthless, but resistance to mask mandates prompted Paul Krugman to accuse the resistant of having “sacralized selfishness.” Around the same time art critic Carolina Miranda was heard to say that toxic individualism is killing us. The Smithsonian distributed educational materials disdaining individualism as whiteness.

, my fellow FAIR in the Arts grantee, was subjected to a workplace training in which it was claimed that said whiteness “divides each and all of us from the earth, the sun, the wind, the water, the stars, [and] the animals that roam the earth.”Newman, on page 158, expresses a wholly opposite view, germane to his art.

When you see a person for the first time, you have an immediate impact. You don’t really have to start looking at detalis. It’s a total reaction in which the entire personality of a person and your own personality make contact…. If you have to stand there examining the eyelashes and all that sort of thing, it becomes a cosmetic situation in which you remove yourself from the experience.

For “eyelashes,” read “skin color.” Or “nose length.” Or what have you.

As Schreyach summarizes it, “The simultaneity of openness and closedness is the condition for scale, the balance of autonomous self and autonomous other.” The attached note remarks that Newman, replying to Harold Rosenberg in 1948, said “that to understand even one of his paintings properly would mean ‘the end of all state capitalism and totalitarianism.’” In isolation that sounds grandiose and far-fetched, but in fact there may be something to it. Abstraction is an art of sound individualism, and sound individuals are resistant to dictatorship.

Content at DMJ is free but paid subscriptions keep it coming. Please consider one for yourself and thank you for reading.

We are in the midst of an Asynchronous Studio Book Club reading of Totality: Abstraction and Meaning in the Art of Barnett Newman by Michael Schreyach. Obtain your copy and jump in. For future titles, see the ASBC schedule.

Dissident Muse’s first publication, Backseat Driver by James Croak, is available now at Amazon.

Aphorisms for Artists: 100 Ways Toward Better Art by Walter Darby Bannard is out now at Allworth Press. More information is available at the site for the book. If you own it already, thank you; please consider reviewing the book at Amazon or B&N.