The Shape of Content (2)

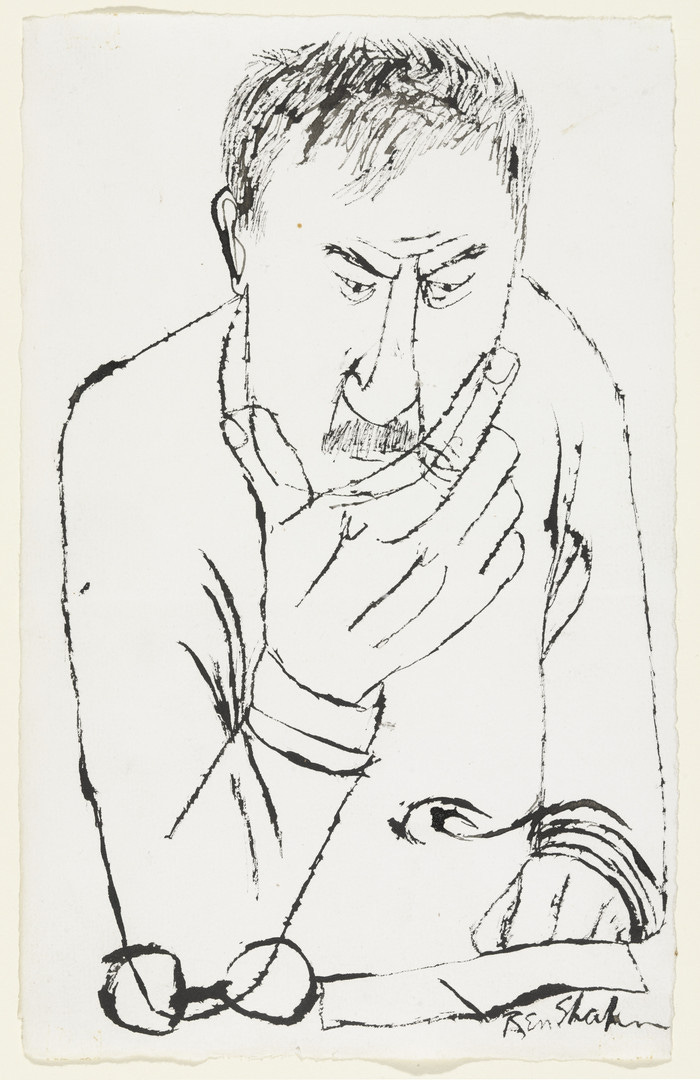

An Asynchronous Studio Book Club reading of The Shape of Content by Ben Shahn.

The chapter “The Shape of Content” in the book of that title starts with the assertion that “Form is the very shape of content.” This might have been an oppositional statement for the kind of critic lampooned on page 56:

“The scheme is of predominantly large areas of whites, ochres, umbers and blacks which break off abruptly into moments of rich blues with underlayers of purple.” Of another artist, it is written: “White cuttings expand and contract, suspended in inky black scaffoldings which alternate as interstices and positive shapes.”

Et cetera. It was 1956, and the North American continent was thick with herds of what Rackstraw Downes once dismissed as Greenbergers. But Clement Greenberg himself would have agreed with Shahn completely. He wrote, in Artforum, in 1967:

One reason among others why the use of the term “formalism” is stultifying is that it begs a large part of the very difficult question as to what can be sensibly said about works of art. It assumes that “form” and “content” in art can be adequately distinguished for the purposes of discourse. This implies in turn that discursive thought has solved just those problems of art upon whose imperviousness to discursive thinking the very possiblity of art depends.

Moreover, “...the quality of a work of art inheres in its ‘content,’ and vice versa. Quality is ‘content.’ You know that a work of art has content because of its effect.” I discussed this at length in an essay I wrote eleven years ago, Vulgarity With A Vengeance: The Clement Greenberg Myth Machine.

On page 60 Shahn segues from Pollock to Mathieu. The latter, he recalls, dressed in a costume of black silk and a white helmet to execute his works. Mathieu was a terrible painter and it’s curious that he used to be taken so seriously. Pollock and Mathieu are lauded as equals in Yoshihara Jirō’s Gutai Manifesto.

Now, interestingly, we find a contemporary beauty in the art and architecture of the past ravaged by the passage of time or natural disasters. Although their beauty is considered decadent, it may be that the innate beauty of matter is reemerging from behind the mask of artificial embellishment. Ruins unexpectedly welcome us with warmth and friendliness; they speak to us through their beautiful cracks and rubble—which might be a revenge of matter that has regained its innate life. In this sense, we highly regard the works of Pollock and Mathieu. Their work reveals the scream of matter itself, cries of the paint and enamel. These two artists confront matter in a way that aptly corresponds to their individual discoveries. Or rather, they even seem to serve matter. Astonishing effects of differentiation and integration take place.

Shahn has an interesting take on abstraction (page 63):

Abstraction is perhaps the most classic of the contemporary points of view. It sometimes seems to have much in common with that art which has sought to reject content, but actually it has not, for in the case of abstraction content is its point of departure, its cure, and its theme. To abstract is to draw out the essence of a matter.

On page 65 he characterizes the content of abstraction expressionism as “the true impulsive compulsive self, revealed in paint.” This is said as a picture maker, but indirectly, he gets it.

His five aspects of form is a worthy mini-manifesto of figurative modernism (page 70):

Form is based, first, upon a supposition, a theme. For is, second, a marshaling of materials, the inert matter in which the theme is to be cast. Form is, third, a setting of boundaries, of limits, the whole extent of idea, but no more, an outer shape of idea. Form is, next the relating of inner shapes to the outer limits, the initial establishing of harmonies. Form is, further, the abolishing of excessive content, of content that falls outside the true limits of the theme. It is the abolishing of excessive materials, whatever material is extraneous to inner harmony, to the order of shapes now established. Form is thus a discipline, an ordering, according to the needs of content.

“On Nonconformity” is my favorite essay in the book. “All art is based upon nonconformity,” he says on page 76, and proves it with a series of quotable lines. “Protestantism in art seems almost to have preceded Protestantism in religion” (p. 78). The artist “must maintain an attitude that is at once detached and deeply involved” (p. 79). He “must never fail to be involved in the pleasures and the desperations of mankind, for in them lies the very source of feeling upon which the work of art is registered” (p. 81). Lorenzetti, Masaccio, Kollwitz, Breughel, Rembrandt, Daumier, Goya—each “stands out as an island of civilized feeling in an ocean of corruption. Civilization has freely vindicated them in everything but their nonconformity” (p. 83). Without the “person of outspoken opinion” (p. 84), society decays. Then this, also on page 84:

But I do not wish to underrate the importance of the conformist himself—or perhaps an apter term would be the conservative. In art, the conservative is the vigorous custodian of the artistic treasures of a civilization, its established values and its tastes—those of the past and even those present ones which have become accepted. Without the conservative we would know little of the circumstances of past art; we would have lost much of its meaning; in fact we would probably have lost most of the art itself. However greatly the creative artist may chafe at entrenched conservatism, it is still quite true that his own work is both sustained and enriched by it.

“Good art does not break with the past,” says the Aphorism. “It breaks with the present by emulating the best of the past. Good art looks new because the artist has recombined something old to make something better.”

“Modern Evaluations” is the weakest essay of the collection. It sounds like he was trying to explain modernist aesthetics to his dentist. But “The Education of the Artist,” the final talk, is a jewel. On pages 113-114 is a long, italicized paragraph that I would offer here in full if the Internet Archive wasn’t down. It is his “capsule recommendation for a course of education” in art. It recommends much living, much reading, much looking, and much making. I will be handing it out to my students from now on, and redoubling my efforts to act accordingly.

Content at DMJ is free but paid subscriptions keep it coming. Please consider one for yourself and thank you for reading.

Our next title in the Asynchronous Studio Book Club is The World of Perception by Maurice Merleau-Ponty. For more information, see the ASBC homepage.

The current exhibition in the Dissident Museum is David Curcio: The Point of the Needle.

Dissident Muse’s first publication, Backseat Driver by James Croak, is available now at Amazon.

Aphorisms for Artists: 100 Ways Toward Better Art by Walter Darby Bannard is out now at Allworth Press. More information is available at the site for the book. If you own it already, thank you; please consider reviewing the book at Amazon, B&N, or Goodreads.

"Good art looks new because the artist has recombined something old to make something better." It may or may not be better, but it need not be. It's enough that it be as good, in its own way.

I discovered half way through this book that it had misbound signatures resulting in duplicate pages from “Artist in Colleges” while missing “On Nonconformity” and “Modern Evaluations”. Reading the balance of the book was valuable, and these quotes jewels from the chapter “The Education of An Artist: “I have mentioned our great American passion for freedom. And now, let me add to that comment that freedom itself is a disciplined thing. Craft is that discipline which frees the spirit; and style is the result.” And: “The primary concern of the serious artist is to get the thing said-and wonderfully well.”