The Creative Act (2)

An Asynchronous Studio Book Club reading of The Creative Act: A Way of Being by Rick Rubin.

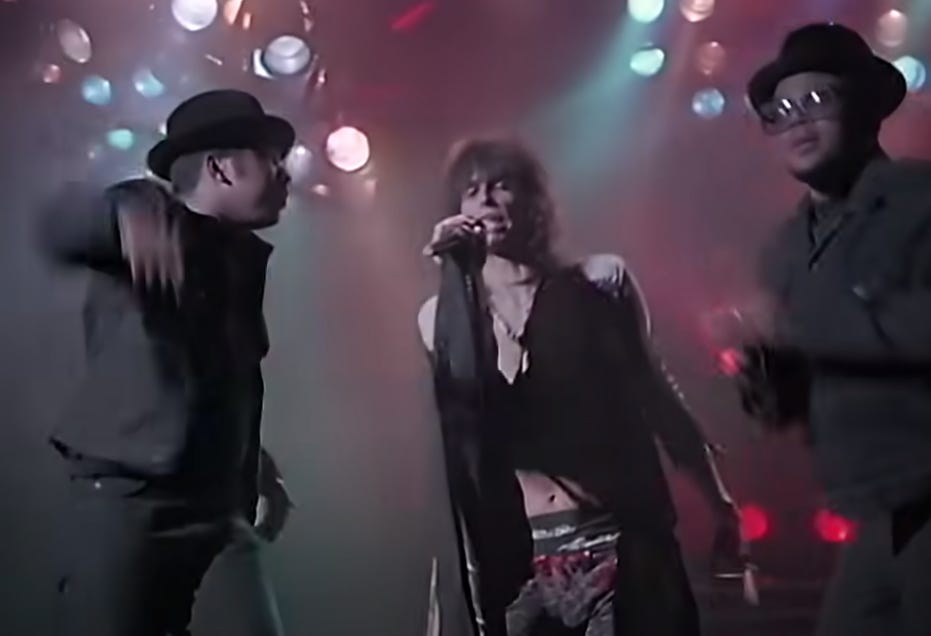

Sirius XM channel Ozzy’s Boneyard features the invaluable show Influenced, in which host Billy Morrison traces recurring musical and thematic tropes across the history of hard rock and metal. His most recent guest was Darryl McDaniels of Run-DMC, who recounted coming into the studio with a rap over a loop from “Walk This Way” by Aerosmith. The producer had an idea: do a straight cover of the song. Run and DMC disdained the suggestion, but their DJ, Jam Master Jay, sided with the producer and told the MCs to get with the program. While they learned the song, the producer contacted Aerosmith to ask if they wanted to collaborate. The result is one of the greatest musical events of the 1980s, Aerosmith’s “Walk This Way” covered by Run-DMC and featuring Aerosmith’s Steve Tyler and Joe Perry.

That producer was Rick Rubin.

Popular music for the last four decades owes an enormous debt to Rubin’s capacious imagination. All of his thoughts on the creative process are worth considering, and many of them ought to be taken to heart.

That said, reading this book cover-to-cover was like eating a fifty-count bag of fortune cookies in one sitting. This writing style, consumed at length, did not leave memorable impressions:

Our capacity grows and stretches to touch the idea that Source is offering up. We accept this responsibility with gratitude, cherish it, and protect it. Acknowledging with humility that it comes from beyond us. More important than us. And not just for us. We are in its service.

This is why we are here. It is the impulse through which humanity evolves. We adapt and grow in order to receive. These inherent abilities made it possible for humans, and for all life, over eons, to survive and thrive in an ever-changing world. And to play our predestined role in advancing the cycle of creation. Supporting the birth of other new and more complex forms. If we choose to participate.

I think Neil Strauss wanted to make the book sound like Rick Rubin talks, while Rubin wanted to avoid making the book about him or his life in the music industry. The combination caused Rubin to seem, at times, like he was intoning from on high, and deprived the book of Rubin’s warmth and humility that are apparent when he presents himself.

Rubin claims to know nothing about music. But his taste, which I define as the ability to detect quality, is extraordinary. He may not play an instrument or know music theory, but he understands music in a general way quite well. Unsurprisingly, his remarks about music are the most interesting passages. The chapter “Breaking the Sameness” has several of them:

There are times when a singer doesn’t connect with a song, like an actor whose line reading falls flat. It can be helpful to create a new meaning or an additional backstory to a song’s lyrics. A love song might sound different if sung to a long-lost soulmate, a partner of thirty years that you don’t get along with, a person you saw on the street but never spoke to, or your mother.

With one artist, I suggested singing a love song written to a woman as a devotional to God instead. We can try many different permutations while singing the same song, without changing any of the lyrics, to see which version brings out the best performance.

And:

A technique we sometimes use in the studio is to turn up the volume on the headphones extremely loud. When every sound explodes in your ears, there’s a natural tendency to play much quieter to restore the balance. It’s a forced perspective change, and can bring out a very delicate performance. Even vocals will be whispered, because anything more than that would be overwhelming. Conversely, to coax someone to sing louder, with more energy, I might ask them to turn the vocal volume down in their headphones so their voice is drowned out by the music. Whatever the situation, if a task is challenging to accomplish, there’s often a way to design the surroundings to naturally encourage the performance you’re striving for.

Compare those to his occasional remarks on painting (below, from “Why Make Art”):

As human beings, we come and go quickly, and we get to make works that stand as monuments to our time here. Enduring affirmations of existence. Michelangelo’s David, the first cave paintings, a child’s finger-paint landscapes—they all echo the same human cry, like graffiti scrawled in a bathroom stall:

I was here.

Or (from “Translation”):

Learning provides more ways to reliably convey your ideas. From our enlarged menu, we can still choose the simplest, most elegant option. Painters like Barnett Newman, Piet Mondrian, and Joseph Albers were classically trained, and they chose to spend their careers exploring simple, monochromatic, geometric shapes.

We just spent a lot of time with Newman and I’m pretty sure he was not trained in any fashion, much less a classical one. He didn’t start painting until he was thirty. Leaving that aside, Rubin doesn’t connect with visual art or fiction or theater like he does with music, impeding a noble project to make this book pertain to creativity in general.

There’s another creative form with which Rubin does connect, namely professional wrestling. He’s a huge fan going back to the days of Roddy Piper. There’s no mention of it in The Creative Act. That was a grave mistake. The Buddhist tone of the copy, culminating in the chapter “The Art Habit (Sangha),” would have been more compelling if it had been peppered with examples of the pageantry and drama of pro wrestling. He admits to watching it eight hours a week; he has no commensurate feelings about geometric abstraction. The lotus is revered as a Buddhist symbol because it blooms, clean and fragrant, from the mud. This book could have used less lotus and more mud.

One can imagine a version of The Creative Act that stuck to its knitting, focusing on episodes in the recording studio from Rubin’s fascinating career and the examples of painters, writers, and wrestlers he knew personally. I believe that book would have generalized naturally, as does Brenda Ueland’s If You Want to Write, or Robert Henri’s The Art Spirit (from which Rubin draws his epigraph).

As for the book we have, I’m keeping it on my shelf, with respect if not reverence. Anyone already immersed in a creative process may find it too remedial. But for the rest of humanity, it’s likely to be helpful. And who knows—anyone already immersed in a creative process knows how it will regularly slap you back down to a beginner level. There’s no harm in having an appropriate reference handy for such moments.

I still like Darby’s book better.

Content at DMJ is free but paid subscriptions keep it coming. Please consider one for yourself and thank you for reading.

Our next book for the Asynchronous Studio Book Club is I Paint What I Want to See by Philip Guston. Obtain your copy and jump in. For more information see the ASBC schedule.

Dissident Muse’s first publication, Backseat Driver by James Croak, is available now at Amazon.

Aphorisms for Artists: 100 Ways Toward Better Art by Walter Darby Bannard is out now at Allworth Press. More information is available at the site for the book. If you own it already, thank you; please consider reviewing the book at Amazon, B&N, or Goodreads.

I'm about 200 pages into Rubin's book. It's difficult for me to evaluate objectively as I'm seeped in Buddhist thought and work in multiple creative channels. I find myself nodding at his observations, but wondering if someone "trying" to venture into something creative would understand. Or if his observations are sticky.

Contrary to his claims that everyone has the ability, I think not. I also think that he needed an editor. There's repetition and occasional wandering. It's all readable, but still, I wonder about its voice. I hear a guru, but question whether gurus can teach creativity. You're either cursed/blessed with the gift from birth or not. Rubin, as accomplished as he is, leaves a certain hollowness in his advice -- then again, it is Rubin or his co-author?

Readable, but ultimately, it repeatedly states the obvious. By repeatedly, I mean over and over. This one won't find a permanent place on my shelf. But, Franklin, a good recommendation as a ASBC read.

To state the obvious first; this was a fast, easy read after Schreyachs’ “Totality”.

Throughout The Creative Act: A Way of Being, I was hoping for more anecdotes from Rubin about the creative process working with musicians. As a life-long music enthusiast, I was looking for them with every turn of the page. As Franklin states: “Unsurprisingly, his remarks about music are the most interesting passages.” When Rubin did, his love and understanding of the creative process producing music was ever present.

Having listened to his lengthy interview with Joe Rogan (there are also many short clips on Instagram and Youtube) he comes across as a guru or mystic. His physical appearance and personality feeds this persona, knowingly or not.This is less obvious in the book, but palpable. He is engaging to the point of making the creative act sound easy. For the uninitiated, it is a book one can easily be taken in by. Perhaps this is a good thing, I’m not sure. I agree with Franklin’s point: “This book could have used less lotus and more mud.”

Rubin draws a somewhat fuzzy distinction between being creative and being an artist. He mentions many ways one can be creative that have nothing to do with art. However, it’s a book which might lead one to think ‘I’m creative , ergo, I am going to be an artist.’

As a painter, I found his ideas about creativity fairly general, but certainly worthy of keeping them in the fore. As Franklin states, The Creative Act may be “too remedial” for some, but there are plenty of insightful observations that are tried and tested.

For critical thinking about painting and criticism, I often reach for Fairfield Porter’s: Art In Its Own Terms” (perhaps a future read for this group?) and Walter Darby Bannard’s Aphorisms for Artist, both written by accomplished painters and critics in their own right. There are others too: Andrew Forge’s Observation: Notation and Hilton Kramer’s The Revenge of The Philistines.

I appreciated Rubin’s Mingus quote: “Making the simple complicated is commonplace. Making the complicated simple, awesomely simple, that’s creativity.”