Clapping on the 1 and 3 of Painting

On the Amy Sherald flap.

This video1 compiles footage of Jeremiah Wright, Dawn Hampton, and Duke Ellington explaining swing.

The first necessity of swing is emphasis on the 2 and 4 beats of a song in 4/4 time. Wright explains that this emphasis is African in origin and differs from the European emphasis on beats 1 and 3. Hampton tells us that snapping on 1 and 3 sounds, as she puts it, “corny.” Then she brings us out of the corn patch and into the city, where it swings, by guiding us to the 2 and 4. Ellington then demonstrates the art of snapping “behind the beat,” as musicians call it. Playing behind the beat means hitting the beat fractions of a second after it lands, instead of directly on it. Ellington explains that the latter is “considered aggressive.” If you can find the 2 and 4 and a sweet behind-the-beat groove, you are at least in the neighborhood of swing. I need not remind you that it don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing.

All this has little to do with subverting the paradigm of European music, or however it would be put by progressive racialists. Ella, Duke, and the entire backing band were well-versed in the European paradigm. Rather, it’s a willingness to use any knowledge available to make better music, regardless of the origin of that knowledge.

Implicit in that willingness is an awareness of the limitations of knowledge when it comes to art. Art requires feeling, at which knowledge can point but can’t capture. Jimi Hendrix couldn’t read music. Nevertheless, he gave us “Voodoo Child.”

As Bonnard said, a painter with charm can acquire power, but not the other way around.

This is to preface my reactions to the decision by Amy Sherald to pull her exhibition from the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. One, she is a bad technician who struggles with drawing and color. Two, she has no intuitive gift for plastic form that would redeem the deficiencies of technique. Three, the veneration of her work in spite of these shortcomings typifies why I’m more excited about listening to music than looking at contemporary art lately.

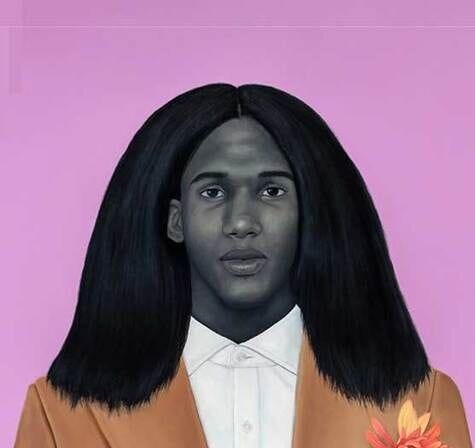

Case in point: NPR illustrated its journalistic tongue bath of Sherald’s latest exhibitions with a photograph of her ten-foot-high 2024 work Trans Forming Liberty as a backdrop for Arewà Basit, who modeled for the painting. More accurately, she modeled for the photograph from which Sherald slavishly derived the painting.

As you can see from the side-by-side comparison, Sherald does not paint skin tones. When Kerry James Marshall uses literal blackness as a symbol of racial blackness, it works because he’s not trying to model form. When Sherald does it, her figures look like they have graphite where their melanin is supposed to be. In her tendency to render skin, hair, and clothing with the same indifferent technique and her lack of engagement with backgrounds, she most resembles Alex Katz, except that she makes Katz look like Courbet. Sherald retroactively justifies Katz’s one-shot method, because look what happens when you meticulously blend the paint—the result is the wearisome aspects of Katz hybridized with the wearisome aspects of Tamara de Lempicka.

Figures in a Marshall are discomfiting by design. Figures in a Sherald are discomfiting in spite of her express intentions that they be sympathetic and representative of the full scope of the American experience. NPR:

Sherald says her subjects are “everyday” Americans. Among them, there’s a Black couple standing proud in front of their car and yellow house, a transgender Statue of Liberty with bright pink hair and a brawny boxer without legs in a ring.

Whether Basit as Lady Liberty represents an everyday American depends, I guess, on what your days are like.

This is, of course, not a depiction of actual America, but a normative vision of America with no white people, and icons of American identity such as the Statue of Liberty and the subjects of Alfred Eisenstaedt’s famous V-J Day photo in Times Square race-swapped with queer blacks.

Whitney Museum curator Rujeko Hockley, said NPR,

…spoke of the “quietly subversive” nature of some of the imagery used by Sherald, like having two Black men restage the iconic World War II photo of a white male sailor kissing a white nurse in Times Square.2 In Sherald’s portrait, the men are both sailors kissing against a blue sky.

But they’re not kissing against a blue sky. They’re kissing against a meaningless single-hue expanse that runs under their feet because Sherald has no idea how to handle backgrounds. We know this because when she attempts to grapple with dimensional space, she looks like a cheap knockoff of Bo Bartlett.

When I call Sherald’s vision normative, I mean reflective of the priorities of postliberal progressive autocracy, as I have written previously: “In this context, ‘diversity’ doesn’t mean diversity, and ‘inclusion’ doesn’t mean inclusion. Instead, those words point to an ethos that reifies an iconic Straight White Man as an effigy of Western culture, and tears down the effigy in order to attack the culture.” Black people live in Bartlett’s painted universe. White people do not live in Sherald’s. Bartlett’s world is inclusive in the real sense. Sherald’s is inclusive in the cynical sense, in that politically fetishized identities fill the whole view. Another reason that Trans Forming Liberty and For Love, and for Country have blank backgrounds is that conceptually, the paintings end at the figures. Race-, sex-, and sexuality-swapping is the entire program.

I am a proponent of free expression, and I dislike the Smithsonian’s mandate to Sherald to replace Trans Forming Liberty with a video of people reacting to Trans Forming Liberty. That was lame and untoward. I respect Sherald’s decision to refuse it, even at the cost of the show. (The Smithsonian subsequently told the WaPo that they discussed pairing the video with the painting, not removing the painting.)

On the other hand, the Smithsonian brought this situation upon itself by pursuing the cynical, DEI conception of inclusion. Postliberal progressivism drives all Smithsonian programming. The Trump administration just announced a review of personnel and communications across eight of its museums because they have become so tendentious. Internally, leadership admitted as much. But the Portrait Gallery was so bad that Trump tried to fire director Kim Sajet back in May. The regents who employ her refused, then quietly pushed her out when it became clear that she had become the stick with which Trump would beat them otherwise, because no one could dispute the president’s characterization of her as a “highly partisan person, and a strong supporter of DEI, which is totally inappropriate for her position.”

The Trump administration has correctly identified the so-called inclusion as a kind of divisiveness. If that inflicts Washington, D.C. museum poobahs with migraines, so be it. Their ranks now include two of the parties responsible for the 2020 cancellation of Philip Guston. In March, Trump issued an executive order that singled out the Smithsonian as having “come under the influence of a divisive, race-centered ideology. This shift has promoted narratives that portray American and Western values as inherently harmful and oppressive.”

Here is Sherald’s “everyday American” legless boxer. It’s possible to agree with all of the following propositions at once: One, black men have been hobbled through no fault of their own in the American arena; two, Sherald’s illustration of this idea is on the nose, unintentionally comic, and inadvertently implicative of messages more racist than I care to describe; three, Trump has a point regarding anti-Americanism at the Smithsonian; and four, doing to the Smithsonian what he did to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting should be on the table, for basically the same reasons—they’re promoting obvious humbug.

Besides, there was already an East Coast iteration of the Sherald show at the Whitney and a West Coast iteration at SFMoMA. The loss of a third iteration is just an abrupt halt to a propaganda campaign. That’s not to say that Sherald herself is a propagandist. Rather, her work became useful to propagandists. You should object to the Smithsonian pushing Sherald for the same reason that you would have objected to the CIA pushing abstract expressionism. The criticism of Sherald is that when her work became useful to propagandists, she developed it to make it even more useful to them. She is the Adolf Ziegler of the regime of postliberal progressive autocracy that was coming into power in America before the second Trump election thwarted it. That said, the denigration of Ziegler as the Meister des Deutschen Schamhaares, the Master of German Pubic Hair, implicitly conceded that he could paint hair.

I saw through the campaign to manufacture Sherald’s canonicity at its inception in 2021. If she were bringing to American painting what Ella Fitzgerald brought to American music, I might remark to myself that that’s how the sausage is made, and forgive the machinations. But the bottom line is that she does not. The paintings of Amy Sherald do not swing. They’re corny. And the people trying to pass them off as the art of our time are not just ideologues—they are profoundly uncool.

Dissident Muse Journal is the blog of Dissident Muse, a publishing and exhibition project by Franklin Einspruch. Content at DMJ is free, but paid subscribers keep it coming. Please consider becoming one yourself, and thank you for reading.

Our next title in the Asynchronous Studio Book Club is Art in America 1945-1970: Writings from the Age of Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and Minimalism, edited by Jed Perl. For more information, see the ASBC homepage.

The current exhibition in the Dissident Museum is David Curcio: The Point of the Needle.

Hat tip Christopher Schwarz.

Why is it “white male sailor” but not “white female nurse”? Sexists.

I used to care more about this sort of thing, but I realized it was unworthy of my caring, which was a waste of time. It is largely a game played by people using art as a means to non-art ends. Let them, since they're going to keep at it as long as it works for them, but don't dignify it with caring.

Great essay.

Boring, stilted, poorly executed agitprop. Corny is the perfect description!!