Art in America 1945–1970 (1)

An Asynchronous Studio Book Club reading of Art in America 1945-1970: Writings from the Age of Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and Minimalism, edited by Jed Perl.

When Art in America 1945-1970 came out in 2014, Dwight Garner called it “a plump, unbuttoned and convivial book, streaked like bacon with gossip and cogitation.” So it is with the first forty pages. The switch from the turgidity of Mark Rothko and the smartypants rhetoric of Barnett Newman to the chirpy recollections of Peggy Guggenheim induces imaginative whiplash.

Reading Rothko is a chore even at a few pages’ length. His nebulous generalizations sometimes lead him to spurious conclusions (p. 5).

A picture lives by companionship, expanding and quickening in the eyes of the sensitive observer. It dies by the same token. It is therefore a risky and unfeeling act to send it out into the world. How often it must be permanently impaired by the eyes of the vulgar and the cruelty of the impotent who would extend their affliction universally!

This artist's statement appeared in a short-lived magazine called “The Tiger’s Eye” in 1947. I prefer sensitive observers to insensitive ones regarding my work as well, but I can’t imagine being so pompous as to think my paintings would be injured by coarse viewing.

Newman has a better flair for prose and a more expansive mind. He concludes a statement from 1949 collected in Selected Writings and Interviews (p. 16):

The love of space is there, and painting functions in space like everything else because it is a communal fact—it can be held in common. Only time can be felt in private. Space is common property. Only time is personal, a private experience. … I insist on my experience of the sensations in time—not the sense of time but the physical sensation of time.

Guggenheim’s history of her Art of This Century Gallery excerpted from her biography spills quite a bit of tea. It begins with her hiring Frederick Kiesler, “a little man about five feet tall, with a Napoleonic complex” to design her space on West 57th Street. I’m prone to complaining when a museum paints an exhibition hall a garish color. For Kiesler, the turquoise floors and ultramarine curtains were just the beginning (p. 19).

In one corridor he placed a revolving wheel to show seven works of Klee. The wheel automatically went into motion when the public stepped across a beam of light. In order to view the reproduction of Marcel Duchamp’s works, you looked through a hole in the wall and turned by hand a very beautiful spidery wheel. The Press named this part of the gallery, Coney Island.

When she closed the gallery, buyers flocked to acquire Kiesler’s architectural gewgaws. Selling Pollocks up to that point had proved impossible. The last straw was a failed gallerina, “a very strange young man who couldn’t type and who never appeared on time—in fact, some days not at all” (p. 28).

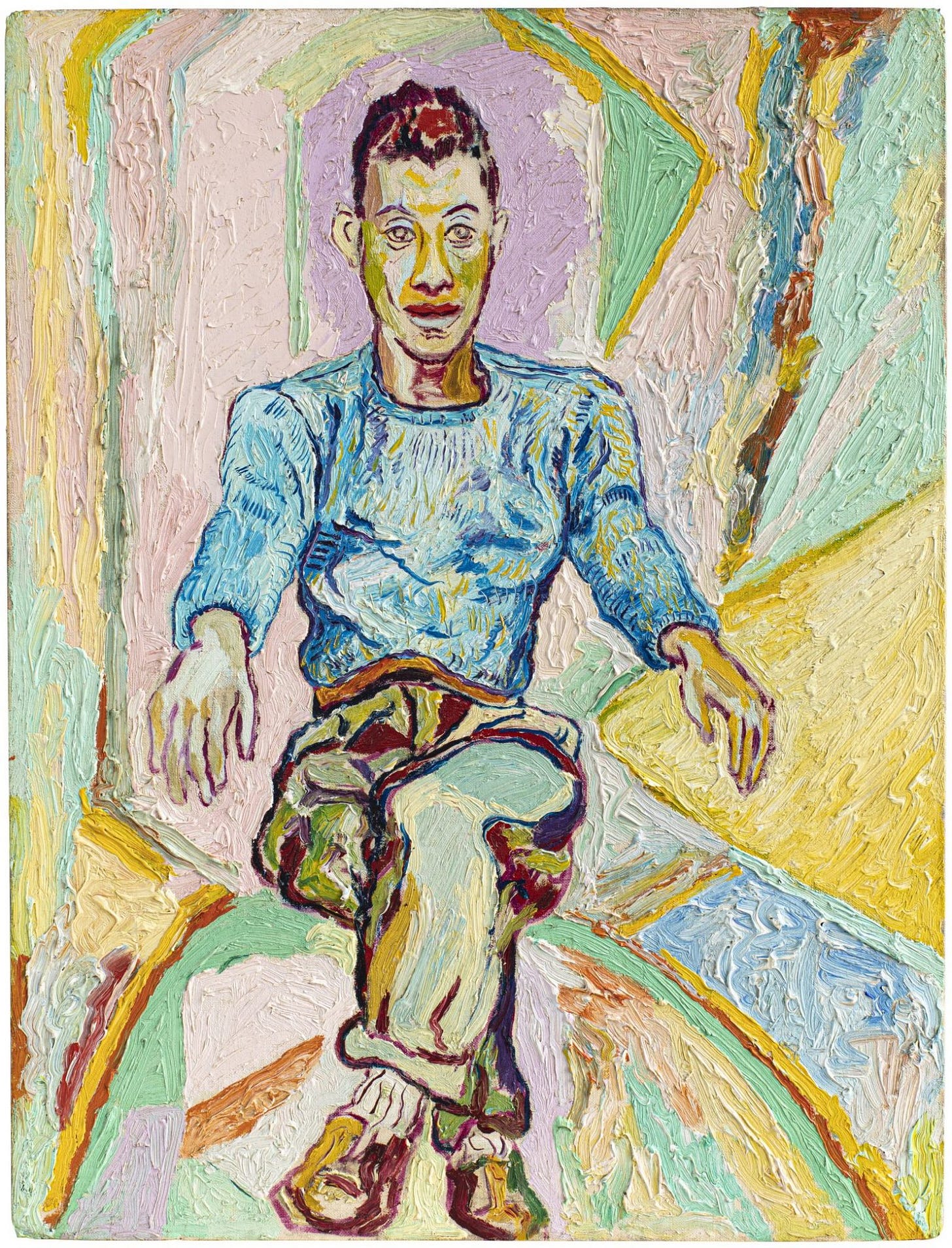

That story was interesting, but Henry Miller’s essay on Beauford Delaney upstages it. Miller tends to make me feel that I’m doing nothing with adequate enthusiasm. Some may find the copy purple, but they will never write an opening paragraph like this:

Yes, he is amazing and invariable, this Beauford. It has been storming now for forty-eight hours, here at Big Sur, and the house is leaking from every cement and stucco pore of its being. That is why my mind dwells on Beauford. How is he faring now in the winter of Manhattan where all is snow and frost? Here it is warm, despite the leaks, despite the gale. We have only one problem—to keep the wood dry. A few sticks of wood in the stove and the place is cosy. But at 181 Greene Street, on that top floor where Beauford works, dreams and eats his paintings, only a roaring furnace kept at a constant temperature of 120 degrees Centigrade can combat the chill of the grave which emanates from the dripping walls, floors and ceilings. And of course there will never be such a furnace at 181 Greene Street. Neither will the sun’s warm rays ever penetrate the single room in which Beauford lives.

Miller compares Delaney’s impoverishment as pitiable even to the typical poor white artist. “…to aspire to greatness, to make pictures which not even intelligent white people can appreciate, that puts him in the category of fools and fanatics.” Nevertheless:

Beauford’s sanity is something to dwell on: it occupies a niche of its own. There are some utterly sane individuals who create the impression that stark lunacy might be a highly desirable state: there are others who make sanity look like a counterfeit cheque, with God the loser. Beauford’s sanity is the sort that one ascribes only to the angels. It never deserts him, even when he is sorely harassed. On the contrary, in crucial moments it grows more intense, more luminous. It never becomes diffracted into bitterness, envy or malice. He sees clearly in good weather and bad, and always warmly, compassionately, understandingly. He sees his own remarkable plight as if it were an object he intended to paint. And if it’s sometimes too cold to paint that plight as he sees it, he simply curls up, pulls the blankets over him, and puts out the light. He has no dialectic up his sleeve, no headache powders, no sedatives, no panaceas. He lives in Greene Street, and his address is always 181, even when he is not there. Even in his dreams it is still 181 Greene Street, the amazing and invariable Beauford DeLaney dreaming, in a temperature just cool enough to keep a fresh corpse fresh.

“Art writing is always a literary mongrel,” writes Perl in the introduction (p. xxi). But if it had a pedigree Miller might have sniffed his nose up at it. Instead he summoned his unruly spirit and gave us one of the great appreciations that any man has ever offered another. I’ve read a lot of Miller, including the delightful but rare volume The Waters Reglitterized, but had never run across his essay on Delaney from Remember to Remember. Perl has accomplished a feat, and thanks to him we now may sample a prodigious buffet.

Content at DMJ is free but paid subscribers keep it coming. They also have access to Dissident Muse Salons, print shop discounts, and Friend on the Road consultations. Please consider becoming one yourself and thank you for reading.

Our current title in the Asynchronous Studio Book Club is Art in America 1945-1970: Writings from the Age of Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and Minimalism by Jed Perl. For more information, see the ASBC homepage.

The current exhibition in the Dissident Museum is David Curcio: The Point of the Needle.

Miller, when writing at his florid peak, out wrote every writer. He's unreadable for paragraphs--sometimes pages--but then, suddenly, he flares brightly like a sun, and as you read, you're stunned. Thanks for excavating these gems.